I've been reading through the stories of the bible (in kids form, for my toddler son), and that's one thing that really strikes me -- the stories think ahead by generations. Often God didn't punish someone by doing anything to them, but their children could not escape consequences.

This ideology has created a class of virtual or literal eunichs. Just like eunichs, they shall have no legacy to pass down. They can't or won't have kids if their own, but they will try to indoctrinate ours so they can keep their ideology going. Therefore it's essential to put the effort into the moral education of our kids at the top of the priority list.

This ideology has created a class of virtual or literal eunichs. Just like eunichs, they shall have no legacy to pass down. They can't or won't have kids if their own, but they will try to indoctrinate ours so they can keep their ideology going. Therefore it's essential to put the effort into the moral education of our kids at the top of the priority list.

There's actually a big problem coming as coal fired power plants continue to be decommissioned: flyash from coal plants is a really useful addition to concrete. It makes it stronger and also helps flowability. As coal power plants go out of service, flyash will no longer be available and so an alternative to this useful material will be required.

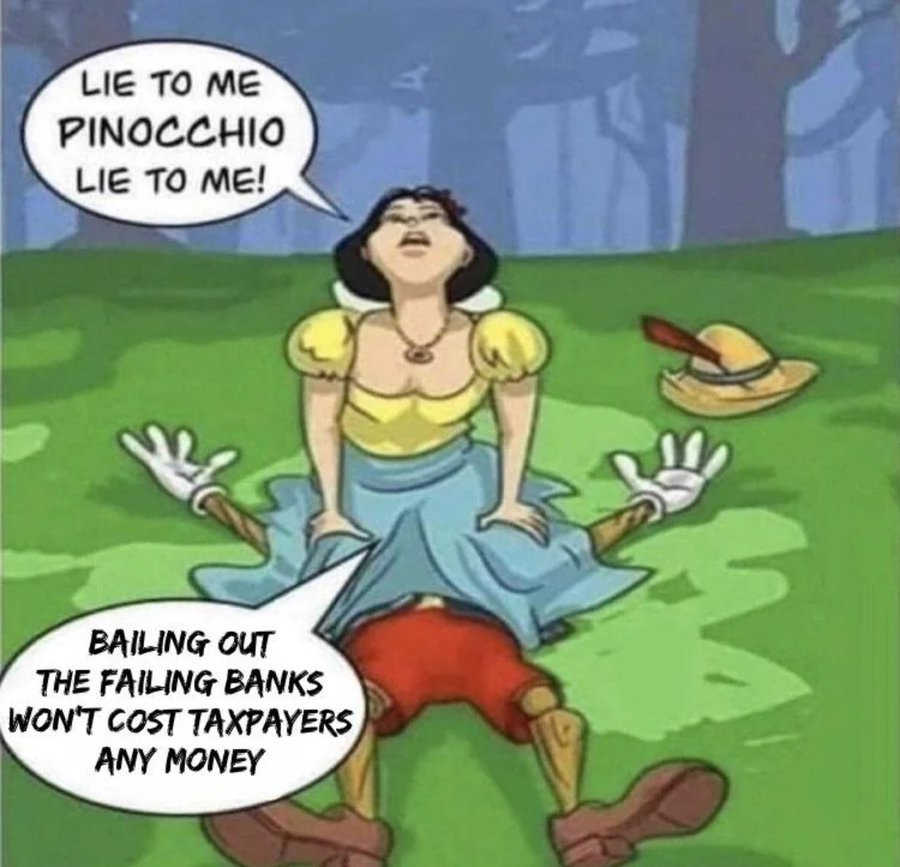

I get a kick out of the fact that I saw some people so happy about the budget that was never going to pass and they knew was never going to pass that had all sorts of things like increasing corporate income tax in it (and by the way if they'd put it on the table 6 months prior they could have voted for while controlling the house, the senate, and the executive but who's counting?), on the same exact day that the government literally gave hundreds of billions of dollars to people who by definition had more than 250,000 dollars in the bank.

My blocklist is empty. I'm not about to change that without a very good reason.

On the other hand, I feel like the moment a corpo makes it onto the Fediverse, it won't be federating with most of it for long.

On the other hand, I feel like the moment a corpo makes it onto the Fediverse, it won't be federating with most of it for long.

I'm an old newb, so I still like #FreeBASIC after all these years.

The standard runtime library is fine most simple programs, and it uses a GCC back-end to compile so it's really not like you're getting any more speed out of it.

The standard runtime library is fine most simple programs, and it uses a GCC back-end to compile so it's really not like you're getting any more speed out of it.

"We need to teach this untrue thing to people!"

Fuck off. A lot of people learned first-hand about the extra workload on their shoulders from their "trying to look busy" coworkers.

Don't get me wrong, some people can work from home very effectively, but *many* cannot, and then they become really annoying little remoras hanging onto you as you're trying to do your job and they're like "oh, I'm off-site, could you do this for me?"

Fuck off. A lot of people learned first-hand about the extra workload on their shoulders from their "trying to look busy" coworkers.

Don't get me wrong, some people can work from home very effectively, but *many* cannot, and then they become really annoying little remoras hanging onto you as you're trying to do your job and they're like "oh, I'm off-site, could you do this for me?"

@004615ce7c74c18d5f4e361407f86976372f6138d22a3a3513fd8dd243611bf6 There we go! Finally managed to follow you from the fediverse too!

Unions are a manifestation of worker power, not the source of it. This misunderstanding leads to people saying a lot of things that are nonsensical.

The decline in unions is in part because of the decline in worker power. That's come about in part because of globalization and in part because of many measures taken over the past 70 years that ensure businesses have the upper hand making workers less valuable and powerful at home as well.

I always like to remind everyone that the powers that be have rooms full of the smartest people on earth trying to figure out how to get you to cheer for the boot on their necks.

The decline in unions is in part because of the decline in worker power. That's come about in part because of globalization and in part because of many measures taken over the past 70 years that ensure businesses have the upper hand making workers less valuable and powerful at home as well.

I always like to remind everyone that the powers that be have rooms full of the smartest people on earth trying to figure out how to get you to cheer for the boot on their necks.

That's true, but let's remember that the right were opposing it the whole time, and the far left were their foot soldiers.

"Banned for questioning the megacorps trying to sell us vaccines"

"Banned for questioning the megacorps trying to sell us vaccines"

There are some really good insights in the article.

Most economists come from eras where economies were growing, which is important -- it's a correlation/causation problem: Did the economists cause the explosion in economies, or did the booming economies allow people to participate in decadent fields such as economics which do not have any productive output to speak of and take credit for something they happened to exist beside?

Stagflation being more complicated than just a relationship between unemployment and inflation, and that would be self-evident to anyone who isn't staring at charts. During the pandemic, unemployment reached massive levels by design, and what happened? Massive inflation. Why? Because lots of dollars were going out and productive capacity was massively slashed by fiat. The fact that lawmakers can do stuff like that and do changes the calculus on its own, forget about times of higher or lower productivity not related to government such as floods or droughts. Economics fails immediately when it decides the real world doesn't exist and only economic theories exist.

Defining economics by nation does harm the real story. In 2006, Ontario was shrinking and Alberta was booming, so Canada was booming. In America, silicon valley was booming while most of the geographical area was destitute. The massive homogenization hides stories of regions that are facing huge problems and mutes stories of other regions being massively successful. On the other hand, many countries are tiny and so that doesn't happen there, and instead one nation looks fantastic while 40 others look destitute.

I don't like the idea that cities are magical or necessarily even good such that they are the unit to go with either. Our current worldview is city-centric to the point that many in cities think everyone should live in cities and it's immoral to do anything else. These people might be shocked to find their raw materials often require the economic output from places there are basically no people.

Confucius traditionally placed farmers and miners above artists and merchants within the societal hierarchy. This view stems from the emphasis Confucianism places on practicality and productivity as essential virtues for a harmonious society. Farmers, as cultivators of the land, were seen as crucial for providing the sustenance necessary for societal stability. Miners, on the other hand, were valued for their contribution to the extraction of valuable resources essential for economic prosperity. In contrast, artists and merchants were often considered less essential, as their professions were seen as less directly tied to the material needs of society.

I'm not saying that we should treat farmers and miners as the top of the social hierarchy, but looking at these powerful engines of economic productivity as merely a vehicle to provide for cities seems like a stretch we have to be very careful of. The factories and supermarkets won't be doing anything without different forms of primary production to create the materials to feed them.

For me, that's why rather than privileging the nation or the city, I'd prefer looking at the region. There are many regions without a city, but there can't be a city that isn't reliant on its surrounding regions for economic inputs. The article itself ends up talking a lot about regions as a concept as well, but then ties it back to the city.

The United States started under this concept, where each region would have a local state and it would be able to manage based on the realities of that region with a very weak national government to tie it together. That changed a lot when Abraham Lincoln fundamentally changed how America worked in the civil war, making the President a much more central figure, and the federal government a much more central power.

I like the concept of monetary policy as a feedback mechanism, but I'm not sure about the specific example provided. Detroit being in decline may or may not mean that it should produce more of its own stuff, it may just mean the city is in decline. I don't think Detroit having its own currency would have changed anything, and I don't know that the argument given is really persuasive -- there's lots of places where they should do more locally, but they don't because of many factors -- Maybe they just aren't industrious, they don't want to, they don't have the capital or the expertise to figure it out. Small nations decline all the time.

The concept of a separated Canada makes a lot of sense to me, to be honest. Toronto dominates the east too much, and Vancouver dominates the west too much. In between there's a landmass the size of Europe that's even more diverse. The idea that a landmass that size is dominated by two superpowered cities is sort of absurd when you think about it.

Some of the ideas of "policies of decline" being pushed at are wrong, however. Subsidizing farmers is entirely self-serving on the part of cities. They're going to need the food no matter what. The option is whether to try to make it cheaper by encouraging production through subsidies, or to let it run at market levels by not subsidizing it. Toronto isn't funding farms because it wants the farmers to feel good, it's funding farms because Toronto requires those crops to be Toronto.

One unfortunate truth is that the economics of big countries sort of mean something different from the politics of big countries. Rome may have eventually collapsed, but it existed in one form or another for over 800 years, 400 years of the roman republic, and another 400 years of the roman empire before finally being crushed.

Meanwhile, Athens the city-state may have existed for near 900 years, but (and this is the key thing) it was under the control of other, larger, more powerful states for most of that. Effectively, the sovereign state is more likely to be able to continue as a larger state than a smaller one, which is why city-states typically don't stick around and nation-states do.

The null hypothesis of "why didn't this person's ideas take off" isn't that experts reviewed and rejected them, but that nobody ever reviewed them. I mean, I don't expect any expert to real The Graysonian Ethic with an eye to integrating any of my ideas into their work. It's just reality -- there's too much to possibly read in a lifetime out there, so people will tend to focus on what seems most important.

Overall, the review of the books was quite interesting and there were some interesting ideas in there. Personally, I like the idea that communities become more self-sufficient and while I don't specifically like cities as a unit of focus, if we change the concepts to be for small regions instead and cities just become a focal point within regions where there's enough economic centralization and specialization to justify them within those regions, the idea of viewing the world that way does help make sense of the world, and I think it would possibly explain why cities exist where they are and don't exist where they aren't, and could help justify why those regional cities should be given a greater focus despite not being another region's megacities.

I to feel like a lot of these ideas are "be careful what you wish for". In a world where cities need to compete for different regions attention and don't just get it by virtue of being the biggest dick in the large arbitrary political unit, I think those underplayed regions suddenly become a lot more powerful. Farming regions without subsidies would likely demand more for their produce, mining regions would likely demand more for their metals and minerals, and a lot of things big cities want won't happen -- I guarantee you the oilsands regions unshackled from the federal and provincial governments would have no interest whatsoever in carbon credits or whatever cockamaney scheme Toronto and Vancouver are trying to cram down everyone else's throat.

Most economists come from eras where economies were growing, which is important -- it's a correlation/causation problem: Did the economists cause the explosion in economies, or did the booming economies allow people to participate in decadent fields such as economics which do not have any productive output to speak of and take credit for something they happened to exist beside?

Stagflation being more complicated than just a relationship between unemployment and inflation, and that would be self-evident to anyone who isn't staring at charts. During the pandemic, unemployment reached massive levels by design, and what happened? Massive inflation. Why? Because lots of dollars were going out and productive capacity was massively slashed by fiat. The fact that lawmakers can do stuff like that and do changes the calculus on its own, forget about times of higher or lower productivity not related to government such as floods or droughts. Economics fails immediately when it decides the real world doesn't exist and only economic theories exist.

Defining economics by nation does harm the real story. In 2006, Ontario was shrinking and Alberta was booming, so Canada was booming. In America, silicon valley was booming while most of the geographical area was destitute. The massive homogenization hides stories of regions that are facing huge problems and mutes stories of other regions being massively successful. On the other hand, many countries are tiny and so that doesn't happen there, and instead one nation looks fantastic while 40 others look destitute.

I don't like the idea that cities are magical or necessarily even good such that they are the unit to go with either. Our current worldview is city-centric to the point that many in cities think everyone should live in cities and it's immoral to do anything else. These people might be shocked to find their raw materials often require the economic output from places there are basically no people.

Confucius traditionally placed farmers and miners above artists and merchants within the societal hierarchy. This view stems from the emphasis Confucianism places on practicality and productivity as essential virtues for a harmonious society. Farmers, as cultivators of the land, were seen as crucial for providing the sustenance necessary for societal stability. Miners, on the other hand, were valued for their contribution to the extraction of valuable resources essential for economic prosperity. In contrast, artists and merchants were often considered less essential, as their professions were seen as less directly tied to the material needs of society.

I'm not saying that we should treat farmers and miners as the top of the social hierarchy, but looking at these powerful engines of economic productivity as merely a vehicle to provide for cities seems like a stretch we have to be very careful of. The factories and supermarkets won't be doing anything without different forms of primary production to create the materials to feed them.

For me, that's why rather than privileging the nation or the city, I'd prefer looking at the region. There are many regions without a city, but there can't be a city that isn't reliant on its surrounding regions for economic inputs. The article itself ends up talking a lot about regions as a concept as well, but then ties it back to the city.

The United States started under this concept, where each region would have a local state and it would be able to manage based on the realities of that region with a very weak national government to tie it together. That changed a lot when Abraham Lincoln fundamentally changed how America worked in the civil war, making the President a much more central figure, and the federal government a much more central power.

I like the concept of monetary policy as a feedback mechanism, but I'm not sure about the specific example provided. Detroit being in decline may or may not mean that it should produce more of its own stuff, it may just mean the city is in decline. I don't think Detroit having its own currency would have changed anything, and I don't know that the argument given is really persuasive -- there's lots of places where they should do more locally, but they don't because of many factors -- Maybe they just aren't industrious, they don't want to, they don't have the capital or the expertise to figure it out. Small nations decline all the time.

The concept of a separated Canada makes a lot of sense to me, to be honest. Toronto dominates the east too much, and Vancouver dominates the west too much. In between there's a landmass the size of Europe that's even more diverse. The idea that a landmass that size is dominated by two superpowered cities is sort of absurd when you think about it.

Some of the ideas of "policies of decline" being pushed at are wrong, however. Subsidizing farmers is entirely self-serving on the part of cities. They're going to need the food no matter what. The option is whether to try to make it cheaper by encouraging production through subsidies, or to let it run at market levels by not subsidizing it. Toronto isn't funding farms because it wants the farmers to feel good, it's funding farms because Toronto requires those crops to be Toronto.

One unfortunate truth is that the economics of big countries sort of mean something different from the politics of big countries. Rome may have eventually collapsed, but it existed in one form or another for over 800 years, 400 years of the roman republic, and another 400 years of the roman empire before finally being crushed.

Meanwhile, Athens the city-state may have existed for near 900 years, but (and this is the key thing) it was under the control of other, larger, more powerful states for most of that. Effectively, the sovereign state is more likely to be able to continue as a larger state than a smaller one, which is why city-states typically don't stick around and nation-states do.

The null hypothesis of "why didn't this person's ideas take off" isn't that experts reviewed and rejected them, but that nobody ever reviewed them. I mean, I don't expect any expert to real The Graysonian Ethic with an eye to integrating any of my ideas into their work. It's just reality -- there's too much to possibly read in a lifetime out there, so people will tend to focus on what seems most important.

Overall, the review of the books was quite interesting and there were some interesting ideas in there. Personally, I like the idea that communities become more self-sufficient and while I don't specifically like cities as a unit of focus, if we change the concepts to be for small regions instead and cities just become a focal point within regions where there's enough economic centralization and specialization to justify them within those regions, the idea of viewing the world that way does help make sense of the world, and I think it would possibly explain why cities exist where they are and don't exist where they aren't, and could help justify why those regional cities should be given a greater focus despite not being another region's megacities.

I to feel like a lot of these ideas are "be careful what you wish for". In a world where cities need to compete for different regions attention and don't just get it by virtue of being the biggest dick in the large arbitrary political unit, I think those underplayed regions suddenly become a lot more powerful. Farming regions without subsidies would likely demand more for their produce, mining regions would likely demand more for their metals and minerals, and a lot of things big cities want won't happen -- I guarantee you the oilsands regions unshackled from the federal and provincial governments would have no interest whatsoever in carbon credits or whatever cockamaney scheme Toronto and Vancouver are trying to cram down everyone else's throat.

People are free to run their instances however they want, but this idea that being defederated is this death sentence is really silly.

I've seen this particularly extreme version where they think nobody will federate with someone they don't like anymore and they'll be all alone on the fediverse, and that seems incredibly narcissistic to me. Like... if you don't want to see the people on that instance, that's fine, but get over yourself.

I've seen this particularly extreme version where they think nobody will federate with someone they don't like anymore and they'll be all alone on the fediverse, and that seems incredibly narcissistic to me. Like... if you don't want to see the people on that instance, that's fine, but get over yourself.

@1da1857506d200e1c4bda3145cd08b7c834f5248fa819df86755a97363d40f1e testing sending to myself.

It doesn't. At all.

The rule of 75 is an accounting and investment tool to help estimate how long it will take for prices to double. It can be used to determine how long it will take for an investment to double if you use growth rate, and it can also be used to estimate how long it will take prices to double if you use the inflation rate.

What you end up doing, is you take the number 75, and you divide it by the growth or inflation rate. What you end up with is the number of years it should take for the prices of something to double and that growth or inflation rate.

If it were true that prices were growing at 2%, then it should take roughly 37.5 years for prices to double. This is not been what people have experienced. As I bring up specific examples, remember that to be matching inflation as it is stated, prices should have doubled within the full lifetime of an older millennial.

The largest component of most people's budgets is going to be rents or mortgages. My first apartment in the 2000s cost me roughly $350 for a two-bedroom place. It was in an apartment building in a pretty nice area of town. Today, in the same city, you cannot rent a place for less than a thousand.

Later on, I was renting a house in the same city. This was around 2012. At that time, that house rental was costing me $785 a month. It was a decent house in a good area of town. Within a couple years, we were kicked out of that place because it was no longer economical for the landlord to be renting it, and by that point you couldn't get a house for less than $1,200 a month.

In the city that I'm in right now, you could buy a nice house for just over $100,000 about 15 years. In fact, my father bought two. In 2015, I bought a house for roughly $220,000 and that was more or less the price of houses in that region at the time. In just those 7 years, my house is already worth $350,000.

So why didn't inflation numbers capture these massive increases in housing costs? The reason that they didn't is that they don't bother checking the cost of the same place. Instead, they use tricks in order to keep the number lower. For example, they use a concept called owner equivalent rent where they ask people who don't rent but own their home how much they would be willing to rent a house similar to what they're living in for. Of course, this is a completely made up number.

Now housing in my region is an unusual example, but it's by far not the only one.

Some bills have massive inflated. High speed internet in my region was $37.50/mo in 2007, but is almost $100/mo today. That's almost 300% in 16 years.

Electricity has doubled since 2007. So has water.

In 1995 gasoline was 60 cents per liter. In 2005 it hit a dollar for the first time. Last year, it hit two dollars for the first time.

Beef has gone up 300% since 2013. Now this goes to another way that they game the system with respect to inflation. Let's say that beef doubles and you can't afford beef anymore, so you start to eat chicken. Well if chicken happens to be the same cost as beef, then they call that substitution and it is considered to cost the same because your cost of living hasn't increased. And then you move from chicken to organ meats, and it costs the same then inflation still hasn't increased for them, even though actual cost of living has gotten much worse and the only reason it doesn't look like that is that you are cutting corners to deal with it. Your quality of life is going down because the cost of living is going up. This is called substitution.

Bread prices have easily doubled. If you went back to 2007 and told people that a normal loaf of bread would cost almost $5, they'd look at you funny.

When I first started using netflix, the service cost about $7 a month. Today, the same service costs $20 a month. In addition, back when I first started using Netflix it was a service with all of the TV shows I wanted to watch. Today, I've got four streaming services to try to get all of my TV shows because the company smelled blood in the water and decided to stop licensing their properties to Netflix and open their own.

Netflix speaks to one of the one-way valves that Central Bank economists use to make inflation numbers look better than they are. In the 2000s, a very good GPU would cost about $400. Today, a very good GPU costs $1,500. iPhones used to be considered fairly expensive at say $400, now the top of the line iPhones are over a thousand. The thing is, the economists who are not paying attention to the fact that things are getting worse price in the fact that your GPU and your iPhone are better than the ones that you would have gotten 15 years ago so that they can ignore the fact that you're spending more for a new iPhone or a new GPU. That adjustment is called hedonic adjustment.

So overall, we have talked about the costs of food, we've talked about the cost of energy, we've talked about the cost of housing, we've talked about the cost of utilities, and all of these have gone up in many cases at least 100% in the past 15 years. Now, perhaps it isn't every single thing, but when some of the largest parts of a family budget are increasing that much in that span of time, a cpi that suggests prices rising at least than half that rate is clearly wrong and given the out in the open "adjustments" that started in the 80s and continued through the 90s. There are websites that track cpi using the pre-1980 cpi calculation, and the previous number is consistently significantly higher.

Now, you might be saying "why would they lie about that? Central banks are independent of the government" -- which is really simple: fudging the numbers upwards is win/win for central banks and the governments who get to hire or fire chairmen and whose legislation authorizes and provides for the central bank. If you can pretend inflation is significantly lower than it is, then real GDP growth looks much higher than it is (would the past 15 years have been recession-free if we added 5% to the CPI? In truth, there would have been few years without a recession), and inflation adjusted payments such as welfare and pension payments or inflation adjusted bonds cost much less, which makes fiscal choices way easier and makes the government generally look more competent. That also means it's easier for the central banks to help keep rates low which means government debt is cheaper and people in general feel wealthier because there's more debt because debt feels good when it's racking up and you have extra money and bad when it's contracting because you need to live with less money than you make to pay down the debt. When politicians are happy and the people feel good, people in charge of central banks tend to be able to keep their jobs.

Illustrating the way central bank chairmen feel about their relationship with the regime, in later interviews Ben Bernanke said he secretly knew the economy was in big trouble in 2006 but didn't want to say anything because he was part of the administration.

The rule of 75 is an accounting and investment tool to help estimate how long it will take for prices to double. It can be used to determine how long it will take for an investment to double if you use growth rate, and it can also be used to estimate how long it will take prices to double if you use the inflation rate.

What you end up doing, is you take the number 75, and you divide it by the growth or inflation rate. What you end up with is the number of years it should take for the prices of something to double and that growth or inflation rate.

If it were true that prices were growing at 2%, then it should take roughly 37.5 years for prices to double. This is not been what people have experienced. As I bring up specific examples, remember that to be matching inflation as it is stated, prices should have doubled within the full lifetime of an older millennial.

The largest component of most people's budgets is going to be rents or mortgages. My first apartment in the 2000s cost me roughly $350 for a two-bedroom place. It was in an apartment building in a pretty nice area of town. Today, in the same city, you cannot rent a place for less than a thousand.

Later on, I was renting a house in the same city. This was around 2012. At that time, that house rental was costing me $785 a month. It was a decent house in a good area of town. Within a couple years, we were kicked out of that place because it was no longer economical for the landlord to be renting it, and by that point you couldn't get a house for less than $1,200 a month.

In the city that I'm in right now, you could buy a nice house for just over $100,000 about 15 years. In fact, my father bought two. In 2015, I bought a house for roughly $220,000 and that was more or less the price of houses in that region at the time. In just those 7 years, my house is already worth $350,000.

So why didn't inflation numbers capture these massive increases in housing costs? The reason that they didn't is that they don't bother checking the cost of the same place. Instead, they use tricks in order to keep the number lower. For example, they use a concept called owner equivalent rent where they ask people who don't rent but own their home how much they would be willing to rent a house similar to what they're living in for. Of course, this is a completely made up number.

Now housing in my region is an unusual example, but it's by far not the only one.

Some bills have massive inflated. High speed internet in my region was $37.50/mo in 2007, but is almost $100/mo today. That's almost 300% in 16 years.

Electricity has doubled since 2007. So has water.

In 1995 gasoline was 60 cents per liter. In 2005 it hit a dollar for the first time. Last year, it hit two dollars for the first time.

Beef has gone up 300% since 2013. Now this goes to another way that they game the system with respect to inflation. Let's say that beef doubles and you can't afford beef anymore, so you start to eat chicken. Well if chicken happens to be the same cost as beef, then they call that substitution and it is considered to cost the same because your cost of living hasn't increased. And then you move from chicken to organ meats, and it costs the same then inflation still hasn't increased for them, even though actual cost of living has gotten much worse and the only reason it doesn't look like that is that you are cutting corners to deal with it. Your quality of life is going down because the cost of living is going up. This is called substitution.

Bread prices have easily doubled. If you went back to 2007 and told people that a normal loaf of bread would cost almost $5, they'd look at you funny.

When I first started using netflix, the service cost about $7 a month. Today, the same service costs $20 a month. In addition, back when I first started using Netflix it was a service with all of the TV shows I wanted to watch. Today, I've got four streaming services to try to get all of my TV shows because the company smelled blood in the water and decided to stop licensing their properties to Netflix and open their own.

Netflix speaks to one of the one-way valves that Central Bank economists use to make inflation numbers look better than they are. In the 2000s, a very good GPU would cost about $400. Today, a very good GPU costs $1,500. iPhones used to be considered fairly expensive at say $400, now the top of the line iPhones are over a thousand. The thing is, the economists who are not paying attention to the fact that things are getting worse price in the fact that your GPU and your iPhone are better than the ones that you would have gotten 15 years ago so that they can ignore the fact that you're spending more for a new iPhone or a new GPU. That adjustment is called hedonic adjustment.

So overall, we have talked about the costs of food, we've talked about the cost of energy, we've talked about the cost of housing, we've talked about the cost of utilities, and all of these have gone up in many cases at least 100% in the past 15 years. Now, perhaps it isn't every single thing, but when some of the largest parts of a family budget are increasing that much in that span of time, a cpi that suggests prices rising at least than half that rate is clearly wrong and given the out in the open "adjustments" that started in the 80s and continued through the 90s. There are websites that track cpi using the pre-1980 cpi calculation, and the previous number is consistently significantly higher.

Now, you might be saying "why would they lie about that? Central banks are independent of the government" -- which is really simple: fudging the numbers upwards is win/win for central banks and the governments who get to hire or fire chairmen and whose legislation authorizes and provides for the central bank. If you can pretend inflation is significantly lower than it is, then real GDP growth looks much higher than it is (would the past 15 years have been recession-free if we added 5% to the CPI? In truth, there would have been few years without a recession), and inflation adjusted payments such as welfare and pension payments or inflation adjusted bonds cost much less, which makes fiscal choices way easier and makes the government generally look more competent. That also means it's easier for the central banks to help keep rates low which means government debt is cheaper and people in general feel wealthier because there's more debt because debt feels good when it's racking up and you have extra money and bad when it's contracting because you need to live with less money than you make to pay down the debt. When politicians are happy and the people feel good, people in charge of central banks tend to be able to keep their jobs.

Illustrating the way central bank chairmen feel about their relationship with the regime, in later interviews Ben Bernanke said he secretly knew the economy was in big trouble in 2006 but didn't want to say anything because he was part of the administration.