As your attorney, I'm gonna have to recommend against eating any components inside your PC, because they're not yummy and some of them taste like medical bills.

On the topic of defining economic systems, I think it's actually reasonable to draw lines to say "this is X" and "this is Y", because otherwise you'll be barking at stuff that doesn't matter.

Communism has certain attributes associated with it. Typically 'communal' ownership of capital that manifests as government control of the means of production in Marxist-Leninist communism (the version of communism typically employed) where the idea is the state is acting as a steward for the proletariat, high levels of central control, a nominal rejection of hierarchy and class, and little to nothing in terms of market economics and high levels of central planning. The close you get to this the closer you get to ideologically pure marxist-leninist communism, and as you fall away from these things the less likely you are to be in communism. There are other forms of communism in theory such as anarcho-communism, and they're equally "real communism", but typically the regimes we've actually seen follow this idea.

Capitalism has certain attributes associated with it, by contrast. Private ownership and control of capital (and capital can be, for example, physical capital like land or factories, financial capital like stocks or bonds, or human capital such as patents or copyright -- though that last one is complicated for reasons I'll discuss imminently) is a core aspect of capitalism, as well as doing business with each other willingly and doing so for mutual benefit (profit motive), limited government interference, there is a class hierarchy in terms of different levels of wealth, as an example of what that might look like generally speaking: the underclass who barely scrape by usually unlawfully, to the working class who work but scrape by, to the middle class who work and can save and acquire capital from their excess wages(Not saying they do, but they can), to the upper classes who don't need to work because they already have capital. While the state can be involved and in practical capitalism must at the minimum act as an arbitrator of property disputes, typically the more the state is involved in a market, the less capitalist it is, and any parts of that market that are solely the purview of the state are not capitalist, though they can (and must for practical purposes) coexist within a largely capitalist framework.

While patents and copyrights are indeed forms of human capital, they are somewhat different in nature because they rely heavily on state enforcement. This ties into broader debates about whether state-granted monopolies, such as patents, are inherently capitalist or distort markets by limiting competition. This shows also how state intervention can muddy the waters about what is or is not "capitalist".

Historically, capitalism is generally represented by the trader class, and more recently by the industrialist class. Traders and the state are often at odds as different groups trying to attain power in a system. There have been times such as during the imperial Chinese where a powerful trader class is totally shut down by fiat. In these times typically inequality does not fall, it's just that the powerful are so because of their positions in other hierarchies such as religion or the state rather than within capitalist class structures. Industrialists are a product of the industrial revolution, and build, own, or operate factories or other industrial works that produce value in that way rather than by finding arbitrage opportunities across geographical regions. More recently still there are new classes such as the financiers who ideally would be helping to get capital from those who have wealth to those who need wealth to operate their businesses (though things can get complex when these systems end up oversized)

Some people say the marxist-leninist states that have existed are "Not real communism", but I think you can look at the definition to help categorize what is and is not "real". One would struggle to suggest that the soviet union wasn't real communism, or that Mao's great leap backwards wasn't real communism, but you could make a convincing argument that after Deng Xiaoping's market reforms "Communist China" actually isn't communist. It's not capitalism by definition, but it has a significant portion of its economy based around generally free markets, I've had to concede that indeed, despite its name, "Communist China" is closer to a centrally managed market economy than anything resembling communism. Some people have called this new thing "market socialism".

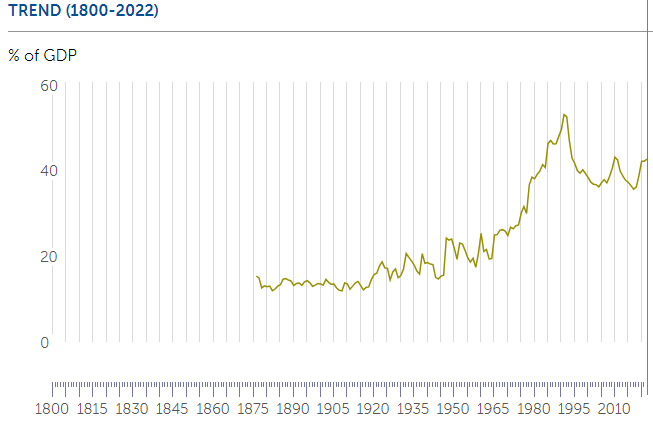

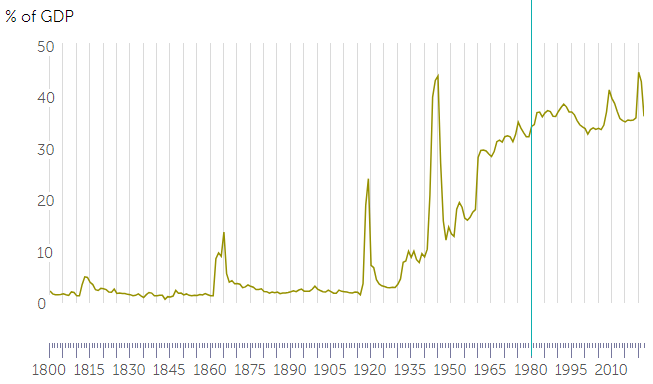

For me, I would argue that the economic system prior to the first world war was largely capitalist. There was very little state intervention in markets. The US government's state spending as proportion of GDP was less than 10%, for example. There was little regulation of the markets. I would certainly consider this "real capitalism", warts and all. The currency was largely not controlled by the government, being backed by gold (or at times silver and gold), so the creation of new dollars was reliant on mining to produce the materials. Mining booms could cause inflation, and busts or other situations where gold left the monetary system could cause deflation.

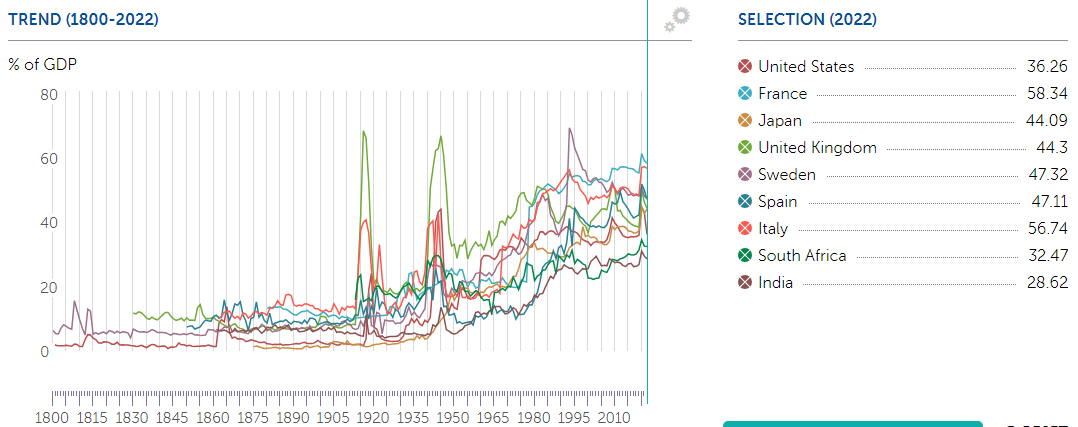

Contrast with today, and I think it's actually very arguable that most developed nations aren't living under "Real Capitalism". There are still elements of capitalism, but consider that the state has grown to be much larger -- for G7 type nations, it's anywhere from 40 to 55% of the economy as state spending. The dollars in circulation exist totally by fiat, and the creation and destruction of the dollars is assigned to a largely fictional system created by the government for this purpose. This spending under the definition I gave above isn't capitalist since it's being spent and controlled directly by the state. Much of the remaining economy is either highly regulated, or highly controlled by the state spending to the point that without that state spending the companies would likely fail, or some combination of both. In the same way that Deng Jiaoping's market reforms made "communist" China "not real communism", I'd argue having so much of the economy under direct control of the government or its proxies means we are living under "not real capitalism". That doesn't mean there aren't elements of the thing, but it's certainly not the same thing as the Pre-WWI economy. Some economists call this new thing "mixed economies".

If you think I'm just chasing some mythical wonderful ideal of capitalism, I'd point you to some of the examples where corporations had way more power than today. The East India company of England took over an entire subcontinent and was so brutal the state actually had to step in and only be slightly incredibly evil and racist, and it was a big step up. The Hudson Bay company in what would eventually become Canada was a huge monopoly and had huge problems. One thing that this demonstrates is actually a potential problem with corporations in the discussion of capitalism, because they are not a real thing -- that is, they are a government construct. In both these cases, the crown created these corporations and granted them monopolies in their regions which they horribly abused. There were shockingly exploitative employers which is one reason why unions came about. There were massive environmental catastrophes that in some cases haven't been resolved even today. Pure capitalism isn't a panacea. But it is actually a thing compared to a thing it is not.

On the topic of the East India company, people who think corporations are uniquely powerful or uniquely bad today should really reconsider because corporations were born bad. You won't find anything Apple or Google are doing today that compares in the least to the East India company before the Crown jumped in to stop it. They can't literally wage war, collect taxes, and govern territories like the East India was empowered to do.

Moreover, the East India company played a primary role in the opium wars in China and the ensuing century of humiliation. It's bad on a level that's hard to articulate.

One of my points in a previous post was that today the state in a typical developed nation is bigger and stronger than ever before as you can see from the 40-60% of GDP that is solely state spending, and corporations aren't as strong as they used to be, using the comparison between the East India company and Google or Apple to show that. We're in an era of the most totalizing state ever, and not just in one country -- virtually everywhere.

Something I've talked a lot about is how collusion between an overly powerful state and capitalists isn't capitalist. It's something else. People go "Oh, but the rich can hire lobbyists!" but you can only drink from a pond that has water in it. (How's that for a proverb?) Capitalists hire lobbyists because the non-capitalist portions of the state can be lucrative if they can be exploited.

There was some crony capitalism even in the "real capitalism" days prior to World War 1, mind you. The state created the railroad robber barons by granting special powers such as eminent domain to individuals so they could build transportation that would be ultimately privately owned. It did get railways built incredibly quickly, but it also meant innocent people got hurt. If the railways needed to be built using "real capitalism", then building the railways would have taken considerably longer and required considerably more money because the railway companies would be forced to negotiate with property owners whose land they wanted to cross from a much weaker bargaining position than "The government says this is mine now, here's some money". It goes to show that even under the most ideal circumstances we must be careful about the power of state intervention and the risks it poses to markets and to individuals. To be clear, you can't pin the robber barons on capitalism, since their powers weren't capitalist but a result of central planing -- the opposite. This aligns with my criticism of neoliberalization and privatization, where the state builds a monopoly then "sells" it to a politically connected individual, passing that monopoly to the new owner, even if that owner could not have created the monopoly on their own without being handed one.

I also want to mention that capitalism and communism are not the only economic systems by a long shot. There's total command economies that are non-communist in nature, such as dictatorships. There's hierarchies such as feudalism which have strict class structures and power comes from the mandate of the king. There's religious socialism which is distinct from Marxist communism. There's hunter gatherer societies where there really isn't an economic system per se, something Marx called Tribal Communism. This further supports my contention that you can have something that isn't communism, or something that isn't capitalism, since it shows there are a lot of things a certain thing can be or not be.

So why does any of this matter? Is it just an exercise in semantics? Why does pinning down definitions help us?

I'd argue the reason the semantics matter is that you can't easily fix a problem you can't define. It's like arguing with your girlfriend and she goes "well if you don't know why I'm mad at you then I'm not going to tell you!" -- good luck mate, without more than that you're not going to be able to make things any better.

It's also important because if we let ourselves be blinded to the true nature of things, we can be pushed into agreeing with decisions that are self-serving to others who pretend to be acting in our best interest. For example, if you say "deregulation is bad because governments give sweetheart deals to their friends and that's capitalism's fault", I'd push back and say "the fact that the government has something to give a sweetheart deal for means it isn't capitalism's fault -- giving more power to the state will make the problem worse, not better".

This applies to the world we live in right now.

For most developed countries, government spending as % of gdp is at or near all-time highs, but prior to World War 1, the state was significantly less of GDP in every single country and we've just seen it go up and up and up.

Some countries have nearly 60% of their economy solely as state spending! 60% of the economy being government isn't capitalism. At best, it's a centrally managed economy.

Your great grandparents probably didn't have to pay much in terms of taxes. They didn't pay land taxes, they didn't pay income taxes. Today, I know I pay a lot in land taxes, and the last dollar I earn is taxed at 50% despite me just being a working class joe.

You might think "Well the government doesn't do anything for me, it only helps its friends in corporations!" -- yeah, exactly as I described. The state and its pawns. The world's richest man Elon Musk got that way by doing the government's bidding. The second richest man Bill Gates got that way by doing the governments bidding too. It's a great success strategy.

Now, you might say "But we need government inflation to pay for roads!" and you'd be wrong. You don't need to inflate the currency to pay for government. In the US from about 1776 to almost the begining of world war 1, the government was paid for with taxation, not inflation. It wasn't until the 1970s when the breton woods monetary system failed that money could be printed with impunity. In the early 1900s, if the US government in particular wanted to make another dollar, they needed 1/35th of an ounce of gold. After World War 2, things changed with the introduction of the breton woods system, but at least in theory the government still needed gold to make a dollar. and while FDR had banned personal ownership of gold, nation-states could still convert their US dollars into gold (which is why the US dollar was called "good as gold"). Nixon suspended the convertibility of gold in the 1970s, and it was only at that point that most world currencies began their race to the bottom.

The fact is, the standard "not real communism" argument is only intended to distance the concept from a situation that looks terrible for communism as an ideology once the wrinkles and blemishes showed up. By contrast, my definition of "real capitalism" obviously embraces the wrinkles and blemishes as part of the end system. Communists claim their system will produce utopia. My definition of communism explicitly explains that capitalism isn't perfect.

Even sort of "utopian capitalists" I've listened to like Peter Schiff will point at stuff like labour abuses and say "Look, not everyone is going to be good. If you're not happy with your job, quit and find an employer better suited to you."

There's an episode of Star Trek: TNG where they're in a nebula or the like and they raise shields, and the ship gets buffeted, and they increased shields and it was more, and they kept on increasing shields, they added warp power to shields, and the ship was getting torn apart, but then they realized they needed to lower shields and then the ship was no longer getting buffeted. It showed that you can't just keep hitting the "more" button. So if a society has a problem that was caused by past state mistakes, you can't just layer on more state and think that's the axiomatic solution. Maybe you need to get the state out of whatever it's screwed up? Now there's plenty of episodes where they need their shields so it isn't like I'm saying there's only one solution to every problem, but the fact that sometimes you're just making things worse the more you act without understanding what's going on is real and important.

Communism has certain attributes associated with it. Typically 'communal' ownership of capital that manifests as government control of the means of production in Marxist-Leninist communism (the version of communism typically employed) where the idea is the state is acting as a steward for the proletariat, high levels of central control, a nominal rejection of hierarchy and class, and little to nothing in terms of market economics and high levels of central planning. The close you get to this the closer you get to ideologically pure marxist-leninist communism, and as you fall away from these things the less likely you are to be in communism. There are other forms of communism in theory such as anarcho-communism, and they're equally "real communism", but typically the regimes we've actually seen follow this idea.

Capitalism has certain attributes associated with it, by contrast. Private ownership and control of capital (and capital can be, for example, physical capital like land or factories, financial capital like stocks or bonds, or human capital such as patents or copyright -- though that last one is complicated for reasons I'll discuss imminently) is a core aspect of capitalism, as well as doing business with each other willingly and doing so for mutual benefit (profit motive), limited government interference, there is a class hierarchy in terms of different levels of wealth, as an example of what that might look like generally speaking: the underclass who barely scrape by usually unlawfully, to the working class who work but scrape by, to the middle class who work and can save and acquire capital from their excess wages(Not saying they do, but they can), to the upper classes who don't need to work because they already have capital. While the state can be involved and in practical capitalism must at the minimum act as an arbitrator of property disputes, typically the more the state is involved in a market, the less capitalist it is, and any parts of that market that are solely the purview of the state are not capitalist, though they can (and must for practical purposes) coexist within a largely capitalist framework.

While patents and copyrights are indeed forms of human capital, they are somewhat different in nature because they rely heavily on state enforcement. This ties into broader debates about whether state-granted monopolies, such as patents, are inherently capitalist or distort markets by limiting competition. This shows also how state intervention can muddy the waters about what is or is not "capitalist".

Historically, capitalism is generally represented by the trader class, and more recently by the industrialist class. Traders and the state are often at odds as different groups trying to attain power in a system. There have been times such as during the imperial Chinese where a powerful trader class is totally shut down by fiat. In these times typically inequality does not fall, it's just that the powerful are so because of their positions in other hierarchies such as religion or the state rather than within capitalist class structures. Industrialists are a product of the industrial revolution, and build, own, or operate factories or other industrial works that produce value in that way rather than by finding arbitrage opportunities across geographical regions. More recently still there are new classes such as the financiers who ideally would be helping to get capital from those who have wealth to those who need wealth to operate their businesses (though things can get complex when these systems end up oversized)

Some people say the marxist-leninist states that have existed are "Not real communism", but I think you can look at the definition to help categorize what is and is not "real". One would struggle to suggest that the soviet union wasn't real communism, or that Mao's great leap backwards wasn't real communism, but you could make a convincing argument that after Deng Xiaoping's market reforms "Communist China" actually isn't communist. It's not capitalism by definition, but it has a significant portion of its economy based around generally free markets, I've had to concede that indeed, despite its name, "Communist China" is closer to a centrally managed market economy than anything resembling communism. Some people have called this new thing "market socialism".

For me, I would argue that the economic system prior to the first world war was largely capitalist. There was very little state intervention in markets. The US government's state spending as proportion of GDP was less than 10%, for example. There was little regulation of the markets. I would certainly consider this "real capitalism", warts and all. The currency was largely not controlled by the government, being backed by gold (or at times silver and gold), so the creation of new dollars was reliant on mining to produce the materials. Mining booms could cause inflation, and busts or other situations where gold left the monetary system could cause deflation.

Contrast with today, and I think it's actually very arguable that most developed nations aren't living under "Real Capitalism". There are still elements of capitalism, but consider that the state has grown to be much larger -- for G7 type nations, it's anywhere from 40 to 55% of the economy as state spending. The dollars in circulation exist totally by fiat, and the creation and destruction of the dollars is assigned to a largely fictional system created by the government for this purpose. This spending under the definition I gave above isn't capitalist since it's being spent and controlled directly by the state. Much of the remaining economy is either highly regulated, or highly controlled by the state spending to the point that without that state spending the companies would likely fail, or some combination of both. In the same way that Deng Jiaoping's market reforms made "communist" China "not real communism", I'd argue having so much of the economy under direct control of the government or its proxies means we are living under "not real capitalism". That doesn't mean there aren't elements of the thing, but it's certainly not the same thing as the Pre-WWI economy. Some economists call this new thing "mixed economies".

If you think I'm just chasing some mythical wonderful ideal of capitalism, I'd point you to some of the examples where corporations had way more power than today. The East India company of England took over an entire subcontinent and was so brutal the state actually had to step in and only be slightly incredibly evil and racist, and it was a big step up. The Hudson Bay company in what would eventually become Canada was a huge monopoly and had huge problems. One thing that this demonstrates is actually a potential problem with corporations in the discussion of capitalism, because they are not a real thing -- that is, they are a government construct. In both these cases, the crown created these corporations and granted them monopolies in their regions which they horribly abused. There were shockingly exploitative employers which is one reason why unions came about. There were massive environmental catastrophes that in some cases haven't been resolved even today. Pure capitalism isn't a panacea. But it is actually a thing compared to a thing it is not.

On the topic of the East India company, people who think corporations are uniquely powerful or uniquely bad today should really reconsider because corporations were born bad. You won't find anything Apple or Google are doing today that compares in the least to the East India company before the Crown jumped in to stop it. They can't literally wage war, collect taxes, and govern territories like the East India was empowered to do.

Moreover, the East India company played a primary role in the opium wars in China and the ensuing century of humiliation. It's bad on a level that's hard to articulate.

One of my points in a previous post was that today the state in a typical developed nation is bigger and stronger than ever before as you can see from the 40-60% of GDP that is solely state spending, and corporations aren't as strong as they used to be, using the comparison between the East India company and Google or Apple to show that. We're in an era of the most totalizing state ever, and not just in one country -- virtually everywhere.

Something I've talked a lot about is how collusion between an overly powerful state and capitalists isn't capitalist. It's something else. People go "Oh, but the rich can hire lobbyists!" but you can only drink from a pond that has water in it. (How's that for a proverb?) Capitalists hire lobbyists because the non-capitalist portions of the state can be lucrative if they can be exploited.

There was some crony capitalism even in the "real capitalism" days prior to World War 1, mind you. The state created the railroad robber barons by granting special powers such as eminent domain to individuals so they could build transportation that would be ultimately privately owned. It did get railways built incredibly quickly, but it also meant innocent people got hurt. If the railways needed to be built using "real capitalism", then building the railways would have taken considerably longer and required considerably more money because the railway companies would be forced to negotiate with property owners whose land they wanted to cross from a much weaker bargaining position than "The government says this is mine now, here's some money". It goes to show that even under the most ideal circumstances we must be careful about the power of state intervention and the risks it poses to markets and to individuals. To be clear, you can't pin the robber barons on capitalism, since their powers weren't capitalist but a result of central planing -- the opposite. This aligns with my criticism of neoliberalization and privatization, where the state builds a monopoly then "sells" it to a politically connected individual, passing that monopoly to the new owner, even if that owner could not have created the monopoly on their own without being handed one.

I also want to mention that capitalism and communism are not the only economic systems by a long shot. There's total command economies that are non-communist in nature, such as dictatorships. There's hierarchies such as feudalism which have strict class structures and power comes from the mandate of the king. There's religious socialism which is distinct from Marxist communism. There's hunter gatherer societies where there really isn't an economic system per se, something Marx called Tribal Communism. This further supports my contention that you can have something that isn't communism, or something that isn't capitalism, since it shows there are a lot of things a certain thing can be or not be.

So why does any of this matter? Is it just an exercise in semantics? Why does pinning down definitions help us?

I'd argue the reason the semantics matter is that you can't easily fix a problem you can't define. It's like arguing with your girlfriend and she goes "well if you don't know why I'm mad at you then I'm not going to tell you!" -- good luck mate, without more than that you're not going to be able to make things any better.

It's also important because if we let ourselves be blinded to the true nature of things, we can be pushed into agreeing with decisions that are self-serving to others who pretend to be acting in our best interest. For example, if you say "deregulation is bad because governments give sweetheart deals to their friends and that's capitalism's fault", I'd push back and say "the fact that the government has something to give a sweetheart deal for means it isn't capitalism's fault -- giving more power to the state will make the problem worse, not better".

This applies to the world we live in right now.

For most developed countries, government spending as % of gdp is at or near all-time highs, but prior to World War 1, the state was significantly less of GDP in every single country and we've just seen it go up and up and up.

Some countries have nearly 60% of their economy solely as state spending! 60% of the economy being government isn't capitalism. At best, it's a centrally managed economy.

Your great grandparents probably didn't have to pay much in terms of taxes. They didn't pay land taxes, they didn't pay income taxes. Today, I know I pay a lot in land taxes, and the last dollar I earn is taxed at 50% despite me just being a working class joe.

You might think "Well the government doesn't do anything for me, it only helps its friends in corporations!" -- yeah, exactly as I described. The state and its pawns. The world's richest man Elon Musk got that way by doing the government's bidding. The second richest man Bill Gates got that way by doing the governments bidding too. It's a great success strategy.

Now, you might say "But we need government inflation to pay for roads!" and you'd be wrong. You don't need to inflate the currency to pay for government. In the US from about 1776 to almost the begining of world war 1, the government was paid for with taxation, not inflation. It wasn't until the 1970s when the breton woods monetary system failed that money could be printed with impunity. In the early 1900s, if the US government in particular wanted to make another dollar, they needed 1/35th of an ounce of gold. After World War 2, things changed with the introduction of the breton woods system, but at least in theory the government still needed gold to make a dollar. and while FDR had banned personal ownership of gold, nation-states could still convert their US dollars into gold (which is why the US dollar was called "good as gold"). Nixon suspended the convertibility of gold in the 1970s, and it was only at that point that most world currencies began their race to the bottom.

The fact is, the standard "not real communism" argument is only intended to distance the concept from a situation that looks terrible for communism as an ideology once the wrinkles and blemishes showed up. By contrast, my definition of "real capitalism" obviously embraces the wrinkles and blemishes as part of the end system. Communists claim their system will produce utopia. My definition of communism explicitly explains that capitalism isn't perfect.

Even sort of "utopian capitalists" I've listened to like Peter Schiff will point at stuff like labour abuses and say "Look, not everyone is going to be good. If you're not happy with your job, quit and find an employer better suited to you."

There's an episode of Star Trek: TNG where they're in a nebula or the like and they raise shields, and the ship gets buffeted, and they increased shields and it was more, and they kept on increasing shields, they added warp power to shields, and the ship was getting torn apart, but then they realized they needed to lower shields and then the ship was no longer getting buffeted. It showed that you can't just keep hitting the "more" button. So if a society has a problem that was caused by past state mistakes, you can't just layer on more state and think that's the axiomatic solution. Maybe you need to get the state out of whatever it's screwed up? Now there's plenty of episodes where they need their shields so it isn't like I'm saying there's only one solution to every problem, but the fact that sometimes you're just making things worse the more you act without understanding what's going on is real and important.

The state spending to GDP graph for New Zealand tells a much different story than most of the world, though I think people still misunderstand that story.

If the state was over 50% of gdp in 1992, and it soaked up all these assets, then it sells them for a song to well connected friends of the state, then that's a symptom of central economic planning being a failure, not of capitalism or neoliberalism per se. If the state didn't try to take over so much of the economy in the first place, it wouldn't have had all these assets to unload. And then who buys the state assets? Who else? Friends or pawns of the state players.

When you rack up your credit cards, it feels good while you do that, but eventually you have to stop and that feels worse than if you never did anything.

"Oh, I bought all these funko pops and pokemon cards, and now I need to get rid of them, and I'm selling them for so much less to my buddy, it must be that I should have hung on to them!" No, you never should have bought those funko pops and pokemon cards in the first place, and when you did sell them, you didn't need to sell them to your buddy.

The other big thing is something I've been talking a lot about lately -- don't blame capitalism for the state. The story here is a story in three acts, of the state running up a tab, the state paying off its tab in ways that were ultimately corrupt, and the aftermath of paying off its tab. The state selling off state assets for a song to political friends isn't capitalism, it's... You know, I don't know what you'd even call it, perhaps state-produced oligarchy. But the state acquires assets and builds a huge public monopoly, hands the monopoly to the "private sector", then people blame capitalism for the monopoly as if the real problem wasn't the state's actions that build that monopoly.

A lot of the countries that faced something like this didn't have a choice back then. Canada had to balance its budget in the 1990s at great painful cost because literally nobody was buying bonds from Canada anymore. There just wasn't a way to get into more debt. So there was a bunch of pain because the state got too big under Trudeau the Elder, and a everyone had to deal with painful tax increases and painful spending cuts. You can say "damn you, neoliberalism and capitalism!" but the problem was in reality a state that was overextended. By the way, that happened to the Soviet Union as well, which is why it collapsed, necessitating a quick sell-off of assets which was done corruptly and resulted in a state engineered oligarchy today.

If the state was over 50% of gdp in 1992, and it soaked up all these assets, then it sells them for a song to well connected friends of the state, then that's a symptom of central economic planning being a failure, not of capitalism or neoliberalism per se. If the state didn't try to take over so much of the economy in the first place, it wouldn't have had all these assets to unload. And then who buys the state assets? Who else? Friends or pawns of the state players.

When you rack up your credit cards, it feels good while you do that, but eventually you have to stop and that feels worse than if you never did anything.

"Oh, I bought all these funko pops and pokemon cards, and now I need to get rid of them, and I'm selling them for so much less to my buddy, it must be that I should have hung on to them!" No, you never should have bought those funko pops and pokemon cards in the first place, and when you did sell them, you didn't need to sell them to your buddy.

The other big thing is something I've been talking a lot about lately -- don't blame capitalism for the state. The story here is a story in three acts, of the state running up a tab, the state paying off its tab in ways that were ultimately corrupt, and the aftermath of paying off its tab. The state selling off state assets for a song to political friends isn't capitalism, it's... You know, I don't know what you'd even call it, perhaps state-produced oligarchy. But the state acquires assets and builds a huge public monopoly, hands the monopoly to the "private sector", then people blame capitalism for the monopoly as if the real problem wasn't the state's actions that build that monopoly.

A lot of the countries that faced something like this didn't have a choice back then. Canada had to balance its budget in the 1990s at great painful cost because literally nobody was buying bonds from Canada anymore. There just wasn't a way to get into more debt. So there was a bunch of pain because the state got too big under Trudeau the Elder, and a everyone had to deal with painful tax increases and painful spending cuts. You can say "damn you, neoliberalism and capitalism!" but the problem was in reality a state that was overextended. By the way, that happened to the Soviet Union as well, which is why it collapsed, necessitating a quick sell-off of assets which was done corruptly and resulted in a state engineered oligarchy today.

I always like to remind people who are like "the rich aren't paying their fair share!" that you could liquidate like 3 of the largest companies in America, and solely use their equity to run the government (you couldn't without losing all the equity in the meantime, but bear with me), and it wouldn't put a dent in the budget and you'd need to liquidate the next 10 largest companies next year, and by year 3 or so you probably wouldn't have enough market cap left on the S&P 500 to keep going.

It's like, you have this beast that's so big and sucks up so much money, you can't possibly feed it.

It's crazy to think about because we all pay so much tax, but our great grandparents often didn't have to pay any direct taxes -- no land taxes, no income taxes.

The Jacobins actually played with taxation like what we have during the French revolution, and it was wildly unpopular and killed (along with unpopular revolutionaries like Robspierre)

People will say the obvious, that the expectations of what the government does have changed dramatically over the past 100 years. The word "expectation" is an odd one though because as an example, the US taxes enough for medical care to provide universal healthcare, but then it just doesn't. Many such cases. The problem isn't limited to the USA, however. Italy for example has an economy composed of 56% state spending. Many countries are near the same levels of spending they saw during the world wars. And what do we get? Demands for more money!

Another thing that happens when the government is so big and takes so much is it chokes out everything else. People can't tithe to the church for example, if they're already paying half their income in various taxes as is the case in many countries. They can't save for a rainy day. They can't donate much to the poor because they are the poor. It becomes a self-fulfilling cycle where wealth is soaked up and makes individuals poorer, and because they're poorer they need more big government interventions to make up for their lack of wealth. Government becomes totalizing whether we like it or not, and that's what my grandfather fought in the world wars to prevent. He died quite bitter at what happened afterwards.

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/exp@FPP/USA/JPN/GBR/SWE/ESP/ITA/ZAF/IND/CAN

It's like, you have this beast that's so big and sucks up so much money, you can't possibly feed it.

It's crazy to think about because we all pay so much tax, but our great grandparents often didn't have to pay any direct taxes -- no land taxes, no income taxes.

The Jacobins actually played with taxation like what we have during the French revolution, and it was wildly unpopular and killed (along with unpopular revolutionaries like Robspierre)

People will say the obvious, that the expectations of what the government does have changed dramatically over the past 100 years. The word "expectation" is an odd one though because as an example, the US taxes enough for medical care to provide universal healthcare, but then it just doesn't. Many such cases. The problem isn't limited to the USA, however. Italy for example has an economy composed of 56% state spending. Many countries are near the same levels of spending they saw during the world wars. And what do we get? Demands for more money!

Another thing that happens when the government is so big and takes so much is it chokes out everything else. People can't tithe to the church for example, if they're already paying half their income in various taxes as is the case in many countries. They can't save for a rainy day. They can't donate much to the poor because they are the poor. It becomes a self-fulfilling cycle where wealth is soaked up and makes individuals poorer, and because they're poorer they need more big government interventions to make up for their lack of wealth. Government becomes totalizing whether we like it or not, and that's what my grandfather fought in the world wars to prevent. He died quite bitter at what happened afterwards.

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/exp@FPP/USA/JPN/GBR/SWE/ESP/ITA/ZAF/IND/CAN

I've talked about this a few times recently, that the amount of money charged by the US government to the taxpayer for medical care is basically as much per capita as Canada or the UK spend to give everyone healthcare.

Some people go "Oh, well we have reasons not to have universal healthcare", and if that's what people want then fine, but it's like... You shouldn't have to pay twice. Either you need private health insurance or you need to pay so much for public healthcare it could give everyone healthcare anywhere else. But it's really messed up that you could pay twice and maybe still not even get the healthcare you need once without going bankrupt.

Some people go "Oh, well we have reasons not to have universal healthcare", and if that's what people want then fine, but it's like... You shouldn't have to pay twice. Either you need private health insurance or you need to pay so much for public healthcare it could give everyone healthcare anywhere else. But it's really messed up that you could pay twice and maybe still not even get the healthcare you need once without going bankrupt.

You can't change something you don't understand, and you've systematically shown your lack of understanding of economics.

Here's a graph of state spending as % of gdp for several countries. knock yourself out.

Here's a graph of state spending as % of gdp for several countries. knock yourself out.

Capitalism is the private ownership and control of capital, free trade, lacking barriers. Once the state starts micro-managing, that's not capitalism anymore. It's something else. Maybe overall the market is more or less capitalist overall, but the state micro-managing markets is definitionally not capitalist.

You can laugh all you want, but it's an important distinction to make. Our problem today is an omnipresent state that is overbearing into every nanometer of our lives. If people get rich off of that, it's just the state rewarding its pawns.

As for the state enforcing property rights, that's part of the problem of pure capitalism, that it can't actually exist because at some point you need to enforce property rights or contracts and the state needs to step in, and every step away from the ideal puts you onto that spectrum. When you get to half the economy being the state and the other half being pawns of the state like we've got, you're well past capitalism, and you can laugh and laugh, but I'll still be correct. I'd be like saying the thing you hate most about fencing is getting shot. If you're getting shot then you're not fencing anymore. "Oh, but I always get shot while fencing, you just don't know what fencing is!"

You can laugh all you want, but it's an important distinction to make. Our problem today is an omnipresent state that is overbearing into every nanometer of our lives. If people get rich off of that, it's just the state rewarding its pawns.

As for the state enforcing property rights, that's part of the problem of pure capitalism, that it can't actually exist because at some point you need to enforce property rights or contracts and the state needs to step in, and every step away from the ideal puts you onto that spectrum. When you get to half the economy being the state and the other half being pawns of the state like we've got, you're well past capitalism, and you can laugh and laugh, but I'll still be correct. I'd be like saying the thing you hate most about fencing is getting shot. If you're getting shot then you're not fencing anymore. "Oh, but I always get shot while fencing, you just don't know what fencing is!"

This whole conversation is very strange... "Capitalist" this, "Capitalist" that, but then "Money printer"

The capitalist can't really print money. They can print disney dollars or tokens in your favorite monetized video game, but those things aren't really currency, just pre-purchased merchandise, an agreement between you and one other vendor. The only entity that can print money That's the state, which is not part of a capitalist system by definition.

Even when the state "participates in capitalism", it's like a planet or a sun -- it warps the space around it, becoming a gravity well. It becomes a new point of reference sucking in and modifying everything around it.

Now you might argue that banks print money because of fractional reserve banking.

Who do you think allows such a strange system to exist? Who made it the basis of the whole monetary system?

That isn't to say that totally hands off capitalism would be utopian or perfect, but very often I see people blaming capitalism for an omnipresent state which intervenes in markets constantly such that you can always feel the pull of its gravity well.

I realized recently that bitcoin's fundamental design is broken, and it will never become the universal money standard people think it will. its fixed volume is part of the problem. If you'll only ever have 21 million of a thing (split up into satoshis), then eventually all the bitcoin that have ever existed will exist, and every time more things can be bought with bitcoin (compared to the basically nothing you can buy now other than fiat currency) each satoshi becomes more and more valuable, so where the problem with the money printer is that it pulls value out of the currency that exists and puts it elsewhere (usually in the state's hands because gravity well), in the case of bitcoin it pulls the value out of the things being bought and put it in the existing currency, so as the economy grows the value of your satoshis grow, and you have ultimately the same problem except instead of the money printers having disproportionate buying power, it's the money havers having disproportionate buying power.

That said, I think crypto could nonetheless be the answer. The ideal would be to have some sort of intelligent daemon who would look at the things being bought and sold with the currency you have and exactly shrink or grow the money supply to keep the relative value of each unit the same. What better daemon than an algorithm everyone agrees upon by downloading a piece of open source software?

So how do you solve the second problem? I think it's by being careful about where the new money supply goes or is taken from. I'm imagining that during times of market cap growth the miners and the users (those who are buying and selling with the currency, not just holding it) would get a little bonus, not a huge amount per transaction but enough to grow the overall supply. When the market cap of the currency falls, you'd have fees go up a bit and the extra be destroyed -- not a huge amount per transaction, but enough to shrink the overall supply.

Unfortunately, such a design has a major problem is it doesn't give people a chance to get insanely wealthy through just grabbing a thousand bitcoin back in 2008 for a few pennies, and it doesn't give the state the chance to get insanely wealthy through just printing so much money everyone becomes poor except them. Its strength as a currency would ultimately be why nobody would feel like championing it.

The capitalist can't really print money. They can print disney dollars or tokens in your favorite monetized video game, but those things aren't really currency, just pre-purchased merchandise, an agreement between you and one other vendor. The only entity that can print money That's the state, which is not part of a capitalist system by definition.

Even when the state "participates in capitalism", it's like a planet or a sun -- it warps the space around it, becoming a gravity well. It becomes a new point of reference sucking in and modifying everything around it.

Now you might argue that banks print money because of fractional reserve banking.

Who do you think allows such a strange system to exist? Who made it the basis of the whole monetary system?

That isn't to say that totally hands off capitalism would be utopian or perfect, but very often I see people blaming capitalism for an omnipresent state which intervenes in markets constantly such that you can always feel the pull of its gravity well.

I realized recently that bitcoin's fundamental design is broken, and it will never become the universal money standard people think it will. its fixed volume is part of the problem. If you'll only ever have 21 million of a thing (split up into satoshis), then eventually all the bitcoin that have ever existed will exist, and every time more things can be bought with bitcoin (compared to the basically nothing you can buy now other than fiat currency) each satoshi becomes more and more valuable, so where the problem with the money printer is that it pulls value out of the currency that exists and puts it elsewhere (usually in the state's hands because gravity well), in the case of bitcoin it pulls the value out of the things being bought and put it in the existing currency, so as the economy grows the value of your satoshis grow, and you have ultimately the same problem except instead of the money printers having disproportionate buying power, it's the money havers having disproportionate buying power.

That said, I think crypto could nonetheless be the answer. The ideal would be to have some sort of intelligent daemon who would look at the things being bought and sold with the currency you have and exactly shrink or grow the money supply to keep the relative value of each unit the same. What better daemon than an algorithm everyone agrees upon by downloading a piece of open source software?

So how do you solve the second problem? I think it's by being careful about where the new money supply goes or is taken from. I'm imagining that during times of market cap growth the miners and the users (those who are buying and selling with the currency, not just holding it) would get a little bonus, not a huge amount per transaction but enough to grow the overall supply. When the market cap of the currency falls, you'd have fees go up a bit and the extra be destroyed -- not a huge amount per transaction, but enough to shrink the overall supply.

Unfortunately, such a design has a major problem is it doesn't give people a chance to get insanely wealthy through just grabbing a thousand bitcoin back in 2008 for a few pennies, and it doesn't give the state the chance to get insanely wealthy through just printing so much money everyone becomes poor except them. Its strength as a currency would ultimately be why nobody would feel like championing it.

ngl, that would force me to go and listen to all her albums so I could find clues that might lead me to One Piece.

The Liberals used to be the center left party, but they're insane left now, and the NDP has always been the insane left party, and they're also insane left. Both parties have been walking around sniffing their own farts like they represent every Canadian and speak with the authority of all Canadians.

The official opposition is the party with the second largest number of seats. They sort of push back against the party in power to keep them honest.

The BQ are the Bloc Quebecois. They're literally separatists, they want Quebec to be its own country. I really want the liberals and NDP to get pantsed so badly that the separatists end up doing better than both parties, a party that got no votes at all outside of quebec, but still earns more seats than either the liberals or the NDP.

It would just be a crowning moment of funny for all these idiots talk of "Canadians want this" "Canadians want that" apparently Canadians want to either be conservative or separate tabarnac!

The official opposition is the party with the second largest number of seats. They sort of push back against the party in power to keep them honest.

The BQ are the Bloc Quebecois. They're literally separatists, they want Quebec to be its own country. I really want the liberals and NDP to get pantsed so badly that the separatists end up doing better than both parties, a party that got no votes at all outside of quebec, but still earns more seats than either the liberals or the NDP.

It would just be a crowning moment of funny for all these idiots talk of "Canadians want this" "Canadians want that" apparently Canadians want to either be conservative or separate tabarnac!

We just need to flip 3 more seats and my dream comes true of a conservative majority with a BQ official opposition.

On the first book was sort of a philosophy book for my son, the one I'm working on right now is a science fiction book set 100 years in the future.

I tend to try to write lots of different things though I will fully admit the science fiction book is going to have very strong philosophical underpinnings.

I tend to try to write lots of different things though I will fully admit the science fiction book is going to have very strong philosophical underpinnings.