Das deuschegagenstandstarkaussprechen

(For those who don't get my highly specific joke, I have created an immensely long German compound word using altavista translate which is for German words that are long and hard to say)

(For those who don't get my highly specific joke, I have created an immensely long German compound word using altavista translate which is for German words that are long and hard to say)

That's how this seems to work, you end up with all of these idiots circle jerking all over each other.

"And what does it even mean to "be good"? Does it mean being passive and not hurting anything or does it mean going on a journey to the bottom of the ocean to save your father from the belly of the whale so you can wash your penis?"

You're making my point for me. Why are the insurance companies to blame when the real problem is the incompetent government who is already getting most of the money? It's taking the money, it's spending the money, it's just not actually doing the job the money implies.

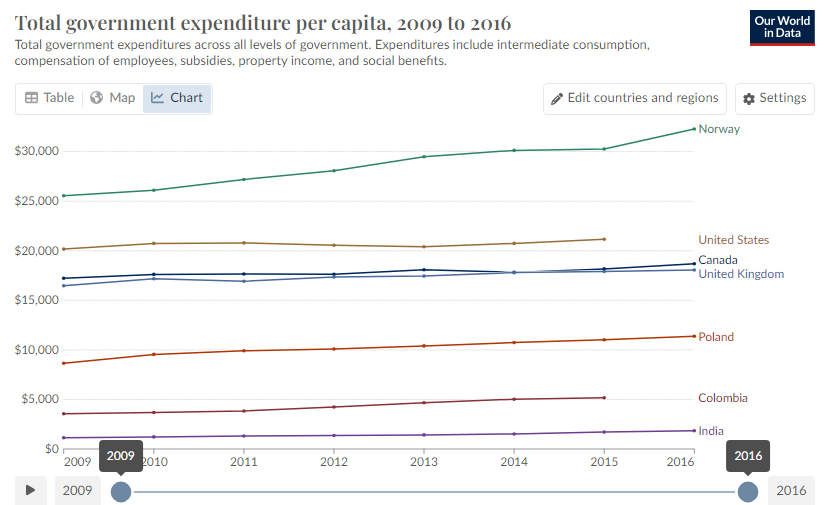

The key here is the per capita government spending is already the same or much more. Whining about NATO doesn't mean anything when the US is already taxing and spending the money. If the US spent significantly less public money on healthcare than other countries I could understand, but it's not.

Scale helps not hurts in this case. In Canada one of the big problems in healthcare is that much of the country is super remote and some of the lowest population density out there so there's a huge number of people who need a charter plane just to have a check up, and so many people are incredibly expensive to the system compared to a higher density country. Canada deals with scale by giving the money to provinces (and it's bigger than the US by land mass)

The key here is the per capita government spending is already the same or much more. Whining about NATO doesn't mean anything when the US is already taxing and spending the money. If the US spent significantly less public money on healthcare than other countries I could understand, but it's not.

Scale helps not hurts in this case. In Canada one of the big problems in healthcare is that much of the country is super remote and some of the lowest population density out there so there's a huge number of people who need a charter plane just to have a check up, and so many people are incredibly expensive to the system compared to a higher density country. Canada deals with scale by giving the money to provinces (and it's bigger than the US by land mass)

The bigger problem of big damn pardons such as Hunter Biden being given an 11 year blanket pardon by Joe Biden this week is political rather than legal.

It's like the George W. Bush era where a lot of stuff he did was legal, but had a huge political price that wrecked the Republican Party for several election cycles. Most people forget the Democrats had a supermajority in the senate for a short time. The overwhelming failure of the Republicans resulted in a lot of Republicans losing their power, and the eventual rise of the populist MAGA movement as a response to the question of "how the hell do we win elections with all the damage we've done?" And the answer turns out to be "dramatic ideologic changes in a core of the party".

Ford pardoning Nixon had a similar political price, helping Tom get Jimmy Carter elected. Reagan changed the story the Republicans were telling that time to win 2 huge terms in office.

Problem is people think digitally today and don't consider things that exist on a continuum between no and yes and things can move a needle without crossing the boundary from one to the other, so politically suicidal actions aren't considered bad since such actions may have worked once or twice proving always yes or always no.

The fact that the sky didn't fall today now that Biden did in fact do that is making digital thinkers think blanket pardons are acceptable now, leading for great calls for blanket immunity for entire lists of people who aligned with the outgoing administration. People are saying Fauci, Liz Cheney, and others should be given similar blanket pardons en masse immediately, before Trump enters office.

The Hunter Biden pardon might be able to be swept under the rug, but blanket immunity for many party loyalists will not. There's only two paths though at that point, ironically: either it turns out to be political suicide to do so for the entire party and nobody does it again, or it doesn't and it'll become routine practice for both parties.

It's like the George W. Bush era where a lot of stuff he did was legal, but had a huge political price that wrecked the Republican Party for several election cycles. Most people forget the Democrats had a supermajority in the senate for a short time. The overwhelming failure of the Republicans resulted in a lot of Republicans losing their power, and the eventual rise of the populist MAGA movement as a response to the question of "how the hell do we win elections with all the damage we've done?" And the answer turns out to be "dramatic ideologic changes in a core of the party".

Ford pardoning Nixon had a similar political price, helping Tom get Jimmy Carter elected. Reagan changed the story the Republicans were telling that time to win 2 huge terms in office.

Problem is people think digitally today and don't consider things that exist on a continuum between no and yes and things can move a needle without crossing the boundary from one to the other, so politically suicidal actions aren't considered bad since such actions may have worked once or twice proving always yes or always no.

The fact that the sky didn't fall today now that Biden did in fact do that is making digital thinkers think blanket pardons are acceptable now, leading for great calls for blanket immunity for entire lists of people who aligned with the outgoing administration. People are saying Fauci, Liz Cheney, and others should be given similar blanket pardons en masse immediately, before Trump enters office.

The Hunter Biden pardon might be able to be swept under the rug, but blanket immunity for many party loyalists will not. There's only two paths though at that point, ironically: either it turns out to be political suicide to do so for the entire party and nobody does it again, or it doesn't and it'll become routine practice for both parties.

You know, I'm Canadian. I live in a country with single payer healthcare, and several members of my family have gotten expensive surgeries that have saved their life or changed their life immeasurably through that system. I and most people in Canada support our single-payer healthcare system because even though it is deeply imperfect, it does what it's supposed to do generally speaking.

You know something interesting about American healthcare?

Americans already pay enough government money to have way better single payer of healthcare than Canadians do. The Canadian government plays roughly 4,500 per person on healthcare. The United States government pays almost twice that.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/283221/per-capita-health-expenditure-by-country/

Of course we do have to admit the data is from 2022, meaning there's some us spending that could remain from covid.

If we go back a few years, Canada and the US are spending roughly the same public money per person on healthcare.

https://ourworldindata.org/government-spending

So the question is: why aren't people pounding the table asking why they don't have the public healthcare they're paying for? The private insurance industry seems to be a stopgap measure, why should they get the lions share of the blame when the they shouldn't exist for the most part in the first place because the Americans already pay full pull for a universal public healthcare system?

It isn't whether they can or not, they already are. What's the use of a private system that is fully publicly funded?

Or demand cuts. If Americans aren't getting universal healthcare, stop charging for universal healthcare.

You know something interesting about American healthcare?

Americans already pay enough government money to have way better single payer of healthcare than Canadians do. The Canadian government plays roughly 4,500 per person on healthcare. The United States government pays almost twice that.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/283221/per-capita-health-expenditure-by-country/

Of course we do have to admit the data is from 2022, meaning there's some us spending that could remain from covid.

If we go back a few years, Canada and the US are spending roughly the same public money per person on healthcare.

https://ourworldindata.org/government-spending

So the question is: why aren't people pounding the table asking why they don't have the public healthcare they're paying for? The private insurance industry seems to be a stopgap measure, why should they get the lions share of the blame when the they shouldn't exist for the most part in the first place because the Americans already pay full pull for a universal public healthcare system?

It isn't whether they can or not, they already are. What's the use of a private system that is fully publicly funded?

Or demand cuts. If Americans aren't getting universal healthcare, stop charging for universal healthcare.

I realized something important about the movie Fight Club.

As has been a recurring theme with my writing lately, Fight Club is a movie from the late 1990s which is seeped in postmodernism.

You can look at Fight club as a story with a 3 act structure:

1. The narrator begins to reject the society he lives in, resulting in meeting Tyler Durden and starting Fight Club.

2. The narrator engages with Tyler's new structure, Project Mayhem, which seems like an evolution of Fight Club after the former tore down all the structures that the people engaging in it lived within.

3. The narrator comes to understand the fact that Project Mayhem is not a good structure for life, acts against it, relying on a more traditional and humanistic model which relies on traditional morality and ultimately returns to some institutions that were lost.

One thing I want to start with is a reminder that in a previous essay, I defined our current era as the "postmodern era". Defining the "modern era" as from roughly the enlightenment to roughly the end of World War 2, the postmodern era began after the end of World War 2 as the western world grappled with the fact that the western world in the modern era which considered itself to be morally, philosophically, technologically, theologically, and practically superior to anything else was able to have first the meat grinder that was World War 1, and second the abomination that was World War 2 and in particular the atrocities of the Germans who were considered the most enlightened people in the modern world.

In Fight Club, we see a world already torn down by postmodernism. Traditional institutions such as the church, family, community, and morality are essentially eliminated, leaving only consumerism as the value that's "allowed" to exist. In this reading, consumerist culture becomes a simulacrum for the sort of fundamental things humans seek. Instead of building a life, the narrator fills his apartment with furniture that represents building a life, a simulacrum of the thing, empty and hollow in practice. "A fridge full of condiments, but no food". He finds some measure of meaning in the support groups for testicular cancer, because although he knows he's fake, the people around him feel real, and he's drawn to that. "Slide", says the talking penguin in his first hallucination, suggesting a fun ride. Marla Singer arriving at the support groups, a woman who is also clearly just as detached and fake as he is, reflects the truth that he doesn't belong in these groups. " 's a lie" she says, similar to the penguin but instead reflecting the truth of the matter in front of him, that even this deeply real thing he's found is for him a simulacrum of meaning because in the same way a floppy disk can save data but a save button shaped like a floppy disk does not, his engagment in the support groups is false even if the support group is real.

The initial solution for the narrator is more postmodernism. Tyler Durden and the narrator end up tearing down consumer culture as one of the last things remaining, tearing down corporate grand narratives, tearing down the civilizational politeness that keeps people from just fighting one another in the streets, and at first that rebellion feels cathartic. In the middle of the first act, the narrator and Tyler attack marriage, "I dunno, get Married." I can't get married...", showing a rejection of other forms of meaning, tradition, and grand narratives.

The second act has Tyler creating Project Mayhem. Project Mayhem is sort of a modern implementation of postmodernism. After wiping away everything and deconstructing everything, the new project combines postmodern deconstruction with a disturbingly modernist impulse for structure and purpose. It’s postmodern in how its entire purpose is to tear down society's structures, hierarchies, and grand narratives. But it’s also modernist in how it operates with military precision, rigid hierarchies, and a clear mission. It is cult-like because unlike postmodernism proper which tore down all meaning and grand narratives, it tore everything down and replaced it with a cult of personality around psychopath Tyler Durden.

One thing that's interesting about both Fight Club and Project Mayhem is that the sort of modernist impulse for structure and purpose is compelling for men, and so even today men end up creating their own Fight Clubs hoping to find meaning in the authenticity of punching another person or taking a punch from another person.

The third act starts as the narrator begins to realize that Project Mayhem is evil. It seeks to tear down existing power structures, but what remains is violent, results in the death of good people, and eventually is revealed to be built upon the ultimate simulacrum -- Tyler Durden himself, who is just a figment of the narrator's imagination. In the face of real consequences from blowing up a bunch of buildings, and the real violence and oppression Project Mayhem reveals to be engaged in, the narrator begins to realize in a sense that there are such a thing as values, meaning, and some measure of sense in the universe. In realizing that such things exist, it becomes the mission of the narrator to engage with the real work of trying to do the right thing and stop the bombs. In the end, what he really needs to do is to reject the nihilistic postmodern impulse embodied in Tyler Durden by symbolically killing himself. At the end of the movie, the narrator is joined by Marla, representing his embrace if not of marriage, of real connection and the institution of some measure of traditional relationships. The last line of the movie, "You met me at a strange time in my life" suggests some measure of resolution to the existential conflict which created Tyler, though the injection of meaning in his life does not necessarily solve all his problems since the bombs go off.

From a certain perspective, our present postmodern establishment can be viewed through a certain lens to resemble Project Mayhem. It too takes a postmodern deconstruction of society and creates a new set of rules, a new hierarchy, a new grand narrative that paradoxically claims to be centered around deconstructing society. Just like Project Mayhem, it creates a global community of acolytes who are willing to engage in horrible acts which violate natural law (violations of human rights, promotion of political violence, harm to innocent individuals or their property) to continue their project in pursuit of a utopia. And just like our narrator, people around the world are starting to reject the modernist implementation of postmodernism because the paradoxes result in negative outcomes. Societies have always tested new ideas, and will continue to, but while the allure of postmodernism was initially quite powerful just like Tyler's Fight club, the damage done by it will be similarly real just like the collapsing credit card buildings at the end of the movie. Similar to the movie, we're starting to see society embrace traditional values once again, wiser through the process of deconstruction and reconstruction.

As has been a recurring theme with my writing lately, Fight Club is a movie from the late 1990s which is seeped in postmodernism.

You can look at Fight club as a story with a 3 act structure:

1. The narrator begins to reject the society he lives in, resulting in meeting Tyler Durden and starting Fight Club.

2. The narrator engages with Tyler's new structure, Project Mayhem, which seems like an evolution of Fight Club after the former tore down all the structures that the people engaging in it lived within.

3. The narrator comes to understand the fact that Project Mayhem is not a good structure for life, acts against it, relying on a more traditional and humanistic model which relies on traditional morality and ultimately returns to some institutions that were lost.

One thing I want to start with is a reminder that in a previous essay, I defined our current era as the "postmodern era". Defining the "modern era" as from roughly the enlightenment to roughly the end of World War 2, the postmodern era began after the end of World War 2 as the western world grappled with the fact that the western world in the modern era which considered itself to be morally, philosophically, technologically, theologically, and practically superior to anything else was able to have first the meat grinder that was World War 1, and second the abomination that was World War 2 and in particular the atrocities of the Germans who were considered the most enlightened people in the modern world.

In Fight Club, we see a world already torn down by postmodernism. Traditional institutions such as the church, family, community, and morality are essentially eliminated, leaving only consumerism as the value that's "allowed" to exist. In this reading, consumerist culture becomes a simulacrum for the sort of fundamental things humans seek. Instead of building a life, the narrator fills his apartment with furniture that represents building a life, a simulacrum of the thing, empty and hollow in practice. "A fridge full of condiments, but no food". He finds some measure of meaning in the support groups for testicular cancer, because although he knows he's fake, the people around him feel real, and he's drawn to that. "Slide", says the talking penguin in his first hallucination, suggesting a fun ride. Marla Singer arriving at the support groups, a woman who is also clearly just as detached and fake as he is, reflects the truth that he doesn't belong in these groups. " 's a lie" she says, similar to the penguin but instead reflecting the truth of the matter in front of him, that even this deeply real thing he's found is for him a simulacrum of meaning because in the same way a floppy disk can save data but a save button shaped like a floppy disk does not, his engagment in the support groups is false even if the support group is real.

The initial solution for the narrator is more postmodernism. Tyler Durden and the narrator end up tearing down consumer culture as one of the last things remaining, tearing down corporate grand narratives, tearing down the civilizational politeness that keeps people from just fighting one another in the streets, and at first that rebellion feels cathartic. In the middle of the first act, the narrator and Tyler attack marriage, "I dunno, get Married." I can't get married...", showing a rejection of other forms of meaning, tradition, and grand narratives.

The second act has Tyler creating Project Mayhem. Project Mayhem is sort of a modern implementation of postmodernism. After wiping away everything and deconstructing everything, the new project combines postmodern deconstruction with a disturbingly modernist impulse for structure and purpose. It’s postmodern in how its entire purpose is to tear down society's structures, hierarchies, and grand narratives. But it’s also modernist in how it operates with military precision, rigid hierarchies, and a clear mission. It is cult-like because unlike postmodernism proper which tore down all meaning and grand narratives, it tore everything down and replaced it with a cult of personality around psychopath Tyler Durden.

One thing that's interesting about both Fight Club and Project Mayhem is that the sort of modernist impulse for structure and purpose is compelling for men, and so even today men end up creating their own Fight Clubs hoping to find meaning in the authenticity of punching another person or taking a punch from another person.

The third act starts as the narrator begins to realize that Project Mayhem is evil. It seeks to tear down existing power structures, but what remains is violent, results in the death of good people, and eventually is revealed to be built upon the ultimate simulacrum -- Tyler Durden himself, who is just a figment of the narrator's imagination. In the face of real consequences from blowing up a bunch of buildings, and the real violence and oppression Project Mayhem reveals to be engaged in, the narrator begins to realize in a sense that there are such a thing as values, meaning, and some measure of sense in the universe. In realizing that such things exist, it becomes the mission of the narrator to engage with the real work of trying to do the right thing and stop the bombs. In the end, what he really needs to do is to reject the nihilistic postmodern impulse embodied in Tyler Durden by symbolically killing himself. At the end of the movie, the narrator is joined by Marla, representing his embrace if not of marriage, of real connection and the institution of some measure of traditional relationships. The last line of the movie, "You met me at a strange time in my life" suggests some measure of resolution to the existential conflict which created Tyler, though the injection of meaning in his life does not necessarily solve all his problems since the bombs go off.

From a certain perspective, our present postmodern establishment can be viewed through a certain lens to resemble Project Mayhem. It too takes a postmodern deconstruction of society and creates a new set of rules, a new hierarchy, a new grand narrative that paradoxically claims to be centered around deconstructing society. Just like Project Mayhem, it creates a global community of acolytes who are willing to engage in horrible acts which violate natural law (violations of human rights, promotion of political violence, harm to innocent individuals or their property) to continue their project in pursuit of a utopia. And just like our narrator, people around the world are starting to reject the modernist implementation of postmodernism because the paradoxes result in negative outcomes. Societies have always tested new ideas, and will continue to, but while the allure of postmodernism was initially quite powerful just like Tyler's Fight club, the damage done by it will be similarly real just like the collapsing credit card buildings at the end of the movie. Similar to the movie, we're starting to see society embrace traditional values once again, wiser through the process of deconstruction and reconstruction.

I think we can agree on two points:

1. The Matrix sequels did at least try to engage with philosophical points, and

2. The Matrix sequels weren't really well executed as works of media, at least not compared to what they could have been.

In a related post shortly after my original Matrix essay, I wrote another short one describing a scene in "reincarnated as a high elf" which is a good example of applied philosophy leading to an earned pay-off. There was not one word said about the power of connections with diverse people, instead you had two people of relatively equal beginning. Both of them were high elves who had memories of being sent to another world, both of them had roughly the same powers as high elves. The battle was won decisively because the MC used all the fruits of the skills he earned through 6 books by engaging with all kinds of people. He used the swordsmanship he learned from his first human love, with a sword he was taught to make by the king of the dwarves, Imbued with magic spells from a mage, using spells he learned from the same, the sword is powered by mana he acquired by rubbing a dragons scale he got by talking to a dragon for 7 months on a mithril armlet he got from the dwarves, and all the spirits he met and befriended along the way came to help. Meanwhile all the other elf had was the angry ghosts of dead soldiers whispering hate in her ear. In the end, he was already strong enough to kill the other high elf, but the spirits responded to his righteous pain over the idea of killing the other high elf, meaning that the final bit of help he got to act with virtue was a result of his virtuous heart. One thing that's really crazy about this fight is it isn't the climactic battle of the book, it's just one vingette near the beginning of the 6th book.

Another great example of a story about rejecting postmodernism whose narrative is integrated that's contemporaneous with The Matrix is Fight Club. The first part of the movie is tearing down all the systems and narratives of the world, the second is a new (and terrible) thing being sucked into the vacuum of meaning that's left, and the third act is the narrator re-establishing that there are values worth fighting for in the world and working to act upon that realization by fighting the nihilistic cult his subconscious pulled him into before he's lost to it.

If anything, whatever the themes it claims to be discussing, the final battle in Matrix: Revolutions is ostensibly about a fight between The One and The Many, which can be an interesting idea, but ultimately there's nothing about the conflict between Neo and Smith that makes use of this idea. Instead it ends up being an existential rant about meaning, and the argument might be that lacking meaning is what ultimately destroys Smith, but it's an unearned payoff, especially compared to these other works. You can interpret the work as actually meaning many different things, but the work itself doesn't ground the things that happen in those ideas, it just talks at you.

In the end, I'm not arguing that The Matrix sequels are intended as monuments to postmodernism. I'm arguing that the Wachowskis ideological grounding in postmodernism which helped the first movie succeed so thoroughly was missing with these other ideologies and as a result the movie isn't really about any of these things, it just says it is. The first movie, however, says it's about postmodernism, and is about that thing.

I'm saving you from my fight club analysis for now because I'm making it a separate effortpost (two, actually...)

1. The Matrix sequels did at least try to engage with philosophical points, and

2. The Matrix sequels weren't really well executed as works of media, at least not compared to what they could have been.

In a related post shortly after my original Matrix essay, I wrote another short one describing a scene in "reincarnated as a high elf" which is a good example of applied philosophy leading to an earned pay-off. There was not one word said about the power of connections with diverse people, instead you had two people of relatively equal beginning. Both of them were high elves who had memories of being sent to another world, both of them had roughly the same powers as high elves. The battle was won decisively because the MC used all the fruits of the skills he earned through 6 books by engaging with all kinds of people. He used the swordsmanship he learned from his first human love, with a sword he was taught to make by the king of the dwarves, Imbued with magic spells from a mage, using spells he learned from the same, the sword is powered by mana he acquired by rubbing a dragons scale he got by talking to a dragon for 7 months on a mithril armlet he got from the dwarves, and all the spirits he met and befriended along the way came to help. Meanwhile all the other elf had was the angry ghosts of dead soldiers whispering hate in her ear. In the end, he was already strong enough to kill the other high elf, but the spirits responded to his righteous pain over the idea of killing the other high elf, meaning that the final bit of help he got to act with virtue was a result of his virtuous heart. One thing that's really crazy about this fight is it isn't the climactic battle of the book, it's just one vingette near the beginning of the 6th book.

Another great example of a story about rejecting postmodernism whose narrative is integrated that's contemporaneous with The Matrix is Fight Club. The first part of the movie is tearing down all the systems and narratives of the world, the second is a new (and terrible) thing being sucked into the vacuum of meaning that's left, and the third act is the narrator re-establishing that there are values worth fighting for in the world and working to act upon that realization by fighting the nihilistic cult his subconscious pulled him into before he's lost to it.

If anything, whatever the themes it claims to be discussing, the final battle in Matrix: Revolutions is ostensibly about a fight between The One and The Many, which can be an interesting idea, but ultimately there's nothing about the conflict between Neo and Smith that makes use of this idea. Instead it ends up being an existential rant about meaning, and the argument might be that lacking meaning is what ultimately destroys Smith, but it's an unearned payoff, especially compared to these other works. You can interpret the work as actually meaning many different things, but the work itself doesn't ground the things that happen in those ideas, it just talks at you.

In the end, I'm not arguing that The Matrix sequels are intended as monuments to postmodernism. I'm arguing that the Wachowskis ideological grounding in postmodernism which helped the first movie succeed so thoroughly was missing with these other ideologies and as a result the movie isn't really about any of these things, it just says it is. The first movie, however, says it's about postmodernism, and is about that thing.

I'm saving you from my fight club analysis for now because I'm making it a separate effortpost (two, actually...)

It's an odd set of messages to send to the pizza delivery app, but I approve, poor thing is probably lonely.

If I was a billionaire I'd probably get a nice farm like Gates keeps doing, but the difference between us is I wouldn't be doing it to make all the poors starve to death in the next recession.

It's kind of a perfect crime when you put it like that. It's like "who shot Mr. Burns" except the baby probably didn't do it.

That's pretty impressive. She had to compete with "Viruses are made by our cells so we can regulate the human body like a factory" Sotomayor.

The one funny cope that I keep seeing is at any father would do it for their son, but feel like if my son was such a fuck up I would think that he should probably spend some time in jail for all of the federal crimes that he committed before he ends up in a ditch. I bet you any money this is part of a long-standing pattern for them, and this is just the latest.

During rittenhouse, I remember the father of one of the idiots who got themselves killed sitting there acting as if their adult child wasn't first of all a massively horrible person with multiple convictions, and second of all presently chasing down an individual who is carrying a gun with the intention of harming that person carrying the gun. I feel for a father who has to go through that, but maybe if you held your kid to a standard a whole bunch of really bad decisions could have been avoided...

During rittenhouse, I remember the father of one of the idiots who got themselves killed sitting there acting as if their adult child wasn't first of all a massively horrible person with multiple convictions, and second of all presently chasing down an individual who is carrying a gun with the intention of harming that person carrying the gun. I feel for a father who has to go through that, but maybe if you held your kid to a standard a whole bunch of really bad decisions could have been avoided...

"I just don't understand people's non-verbal cues! That's why I decided I had to break into the computers in the hospital and sell what I found on the dark web to the Chinese! If only I had understood nonverbal cues!!!"

In my previous essay, I made the point that the first Matrix movie was the only one that was competently executed, and that is because the first movie is an anthem to postmodernism and that was the water in which the Wachowski fish swim, and they are made up of the same matter as the river thereby. The hero's journey is to understand that the world in front of him is a lie and it's only by rejecting the narrative his senses give him and embracing a literal deconstruction of reality in terms of the symbols of the matrix he sees near the end of the movie does he find the power to tear down the systems, and the final monologue is a proud statement that Neo will tear down the existing systems and reveal the falseness of the narratives.

The second and third movies were a mess in part because while they engage with philosophies, the movies don't really integrate those ideas in the same way the first movie integrated postmodernism. In my essay I proposed a second and third movies that would focus on Neo utilizing his inherent virtues as a hero to overcoming the challenges ahead of him. This would be what sequels rejecting postmodernism would look like in my view.

The second movie introduced a new power -- Neo's ability to interact with machines outside of the Matrix. This new power is a synecdoche, where a part represents the whole, of the problems with the movies. why does Neo have this power? Because the movie wanted him to have the power. Practically, there is no explanation for this power given the logistical hurdles of wirelessly manipulating machines. Philosophically, there is no connection between this power and the themes presented of the Matrix being the false simulacrum of the peak of human civilization and Zion being the Desert of the Real. Morally, there was no reason the he deserved this new power, he didn't engage in virtuous conduct to achieve it. It was a deliberate decision which was made ostensibly for the spectacle of it. The story and the narrative find themselves at a crossroads because the actions within the story and the narrative within the story are at odds, and that is a theme throughout the second and third movies, a disconnect between the themes and the events of the movies.

Instead, we got obtuse philosophical dissertations and action scenes that lacked any meaning. After the Architect scene, Neo "chooses love over logic" which has emotional weight, but lacks philosophical grounding and doesn't actually have any moral weight because it isn't clear that choosing to save his lover is the right thing to do, and his passivity limits the moral conviction he shows.

The sequels pivot from postmodernism to systems theory, free will versus determinism, and the cyclical nature of oppression and rebellion, but ultimately there is a difference between narrative and story, and I think that's best illustrated by the difference between the high-minded philosophical concepts spoken of in for example the Architects dissertation, and the actual themes the actions within the movie demonstrate. The themes are discussed but never actually integrated into the plot.

Another theme they somewhat ham-handedly tried to include was the idea of Neo as a messianic figure. They used the imagery at the end of the movie to imply that Neo was an embodiment of Justice and Christ-like, but the narrative is not the story and the trilogy doesn't really support this viewing.

The disconnect between narrative, the story, and the actions of the story makes the addition of philosophical ideas weak, and arguably serves to distract from the core themes of the story as such. If the addition of philosophical ideas was firmly rooted in the core construction of the trilogy then it could have been one of the smartest and best trilogies of all time, but most people found the sequels pretentious, bombastic, and boring because it's ultimately just a bunch of things that happen with little holding the events together once you start ignoring the dissertations on philosophy peppered throughout.

Contrast with the first movie which is explictly about postmodernism, and has a "real world" that's gritty and ugly and boring and a "Matrix" which is sexy, stylized, and exciting, and the core journey for the hero was to learn to deconstruct the world around him and to reject the narrative of the machines, with one of the main enemies in the story being someone who has been released from Platos cave but wants to return and never know the sun.

To your point about Debord's works criticizing spectacle, the Wachowskis neglected to give Neo an integrated arc by exploring the boundaries of his powers in ways that reflect his virtues or philosophical growth. We have many great examples of this in media, where the hero's journey is quiet and reflective instead of loud and reactive. Instead, they leaned on spectacle, which felt like a regression rather than an evolution.

The original Matrix movie is so powerful that today its imagery is used as shorthand for major political movements (The Red Pill). The second and third movies by contrast were ephemeral, and nobody talks about them much today except to mention that they weren't very good. Nobody uses Colonel Sanders, extended rave sequences, stopping robots with your mind or Neo-Jesus as metaphors for anything. that's in spite of the fact that we're in a world that wants meaning and is seeking it desperately. This helps illustrate the difference between them.

One argument could be made that the disjointedness of the sequels was intentional or that the big dumb action scenes were intended to be hollow and meaningless as an intentional philosophical statement. I tend to think neither of these are true based on how self-satisfied the writing seems to be, and how the cinematography really seems to want to convince you that the big dumb action scenes are actually interesting and cool (for example, the slow motion focus on a cool flip from Trinity in Matrix Reloaded). It would suggest that there's further disconnects within the movie where the visual language it's using aren't consistent with the message allegedly being portrayed. Contrast with a highly philosophical piece such as Spec Ops: The Line, which starts off playing things straight but slowly changes the character of how it is portrayed to enhance the discomfort the player would be feeling from the actions the player character has taken in the player's name.

As Morpheus said in the first movie, "Quit trying to hit me and hit me!" -- If the movies were doing their job as implementations of a compelling philosophical framework, they would be engaging through the embodiment of those values. Instead, the movies are boring to watch even during the most incredibly choreographed fight scenes (and one could argue that it was intentional, but I'd counter that the cinematography didn't imply it was intentional, it seemed to imply "you should think this is really cool and epic"). This likely wasn't what they were aiming for, but instead was a symptom of a Hollywood that by this time was starting to be disconnected from the material world and like a car stuck in the snow continued to push the gas harder hoping to move forward but instead just digging a deeper rut in the ice.

So given this perspective, what do you think makes the sequels a cohesive and integrated whole that is greater than the sum of its parts? How does one great movie and two poor movies equal three great movies as a whole? How do you counter the criticism that instead of leaning back from spectacle they instead leaned into it with action sequences that were ultimately boring and hollow in ways that harm the piece instead of helping them?

The second and third movies were a mess in part because while they engage with philosophies, the movies don't really integrate those ideas in the same way the first movie integrated postmodernism. In my essay I proposed a second and third movies that would focus on Neo utilizing his inherent virtues as a hero to overcoming the challenges ahead of him. This would be what sequels rejecting postmodernism would look like in my view.

The second movie introduced a new power -- Neo's ability to interact with machines outside of the Matrix. This new power is a synecdoche, where a part represents the whole, of the problems with the movies. why does Neo have this power? Because the movie wanted him to have the power. Practically, there is no explanation for this power given the logistical hurdles of wirelessly manipulating machines. Philosophically, there is no connection between this power and the themes presented of the Matrix being the false simulacrum of the peak of human civilization and Zion being the Desert of the Real. Morally, there was no reason the he deserved this new power, he didn't engage in virtuous conduct to achieve it. It was a deliberate decision which was made ostensibly for the spectacle of it. The story and the narrative find themselves at a crossroads because the actions within the story and the narrative within the story are at odds, and that is a theme throughout the second and third movies, a disconnect between the themes and the events of the movies.

Instead, we got obtuse philosophical dissertations and action scenes that lacked any meaning. After the Architect scene, Neo "chooses love over logic" which has emotional weight, but lacks philosophical grounding and doesn't actually have any moral weight because it isn't clear that choosing to save his lover is the right thing to do, and his passivity limits the moral conviction he shows.

The sequels pivot from postmodernism to systems theory, free will versus determinism, and the cyclical nature of oppression and rebellion, but ultimately there is a difference between narrative and story, and I think that's best illustrated by the difference between the high-minded philosophical concepts spoken of in for example the Architects dissertation, and the actual themes the actions within the movie demonstrate. The themes are discussed but never actually integrated into the plot.

Another theme they somewhat ham-handedly tried to include was the idea of Neo as a messianic figure. They used the imagery at the end of the movie to imply that Neo was an embodiment of Justice and Christ-like, but the narrative is not the story and the trilogy doesn't really support this viewing.

The disconnect between narrative, the story, and the actions of the story makes the addition of philosophical ideas weak, and arguably serves to distract from the core themes of the story as such. If the addition of philosophical ideas was firmly rooted in the core construction of the trilogy then it could have been one of the smartest and best trilogies of all time, but most people found the sequels pretentious, bombastic, and boring because it's ultimately just a bunch of things that happen with little holding the events together once you start ignoring the dissertations on philosophy peppered throughout.

Contrast with the first movie which is explictly about postmodernism, and has a "real world" that's gritty and ugly and boring and a "Matrix" which is sexy, stylized, and exciting, and the core journey for the hero was to learn to deconstruct the world around him and to reject the narrative of the machines, with one of the main enemies in the story being someone who has been released from Platos cave but wants to return and never know the sun.

To your point about Debord's works criticizing spectacle, the Wachowskis neglected to give Neo an integrated arc by exploring the boundaries of his powers in ways that reflect his virtues or philosophical growth. We have many great examples of this in media, where the hero's journey is quiet and reflective instead of loud and reactive. Instead, they leaned on spectacle, which felt like a regression rather than an evolution.

The original Matrix movie is so powerful that today its imagery is used as shorthand for major political movements (The Red Pill). The second and third movies by contrast were ephemeral, and nobody talks about them much today except to mention that they weren't very good. Nobody uses Colonel Sanders, extended rave sequences, stopping robots with your mind or Neo-Jesus as metaphors for anything. that's in spite of the fact that we're in a world that wants meaning and is seeking it desperately. This helps illustrate the difference between them.

One argument could be made that the disjointedness of the sequels was intentional or that the big dumb action scenes were intended to be hollow and meaningless as an intentional philosophical statement. I tend to think neither of these are true based on how self-satisfied the writing seems to be, and how the cinematography really seems to want to convince you that the big dumb action scenes are actually interesting and cool (for example, the slow motion focus on a cool flip from Trinity in Matrix Reloaded). It would suggest that there's further disconnects within the movie where the visual language it's using aren't consistent with the message allegedly being portrayed. Contrast with a highly philosophical piece such as Spec Ops: The Line, which starts off playing things straight but slowly changes the character of how it is portrayed to enhance the discomfort the player would be feeling from the actions the player character has taken in the player's name.

As Morpheus said in the first movie, "Quit trying to hit me and hit me!" -- If the movies were doing their job as implementations of a compelling philosophical framework, they would be engaging through the embodiment of those values. Instead, the movies are boring to watch even during the most incredibly choreographed fight scenes (and one could argue that it was intentional, but I'd counter that the cinematography didn't imply it was intentional, it seemed to imply "you should think this is really cool and epic"). This likely wasn't what they were aiming for, but instead was a symptom of a Hollywood that by this time was starting to be disconnected from the material world and like a car stuck in the snow continued to push the gas harder hoping to move forward but instead just digging a deeper rut in the ice.

So given this perspective, what do you think makes the sequels a cohesive and integrated whole that is greater than the sum of its parts? How does one great movie and two poor movies equal three great movies as a whole? How do you counter the criticism that instead of leaning back from spectacle they instead leaned into it with action sequences that were ultimately boring and hollow in ways that harm the piece instead of helping them?

I went all-in on the fediverse when I realized you could be shadowbanned on establishment platforms at any time.

People who read my posts might disagree with them (or might not read them because they're too long), but a post talking about how the reason the matrix sequels sucked was because the wachowskis are postmodernists isn't exactly calling for desu desu to the juice.

People who read my posts might disagree with them (or might not read them because they're too long), but a post talking about how the reason the matrix sequels sucked was because the wachowskis are postmodernists isn't exactly calling for desu desu to the juice.